Consideration of Grappling & Wrestling in Renaissance Fencing

Part 1

By John Clements, ARMA Director

Editor’s Note: The reader should note that

this article contains some quotations taken from old English whose spelling

is quite different

from our modern counterpart.  The

skills of grappling and the art of wrestling have a long legacy in Europe.

In the early 1500s, many soldiers, scholars, priests, and nobles wrote

that wrestling was important in preparing aristocratic youth for military

service. The detailed depictions of unarmed techniques in many Medieval

fencing manuals (such as those by Fiore Dei Liberi and Hans Talhoffer)

are well known and accounts of wrestling and grappling abound in descriptions

of 15th century tournaments and judicial contests. A 1442 tournament

fight in Paris "with weapons as we are accustomed to carrying in

battle" included in its fourth article the stipulation "that

each of us may help each other with wrestling, using legs, feet, arms

or hands." English knightly tournaments as late as 1507 allowed

combatants "To Wrestle all maner of wayes" or to fight "with

Gripe, or otherwise". The Hispano-Italian master Pietro Monte in

the 1480’s even recognized wrestling as the "foundation of

all fighting", armed or unarmed. Albrecht Duerer’s Fechtbuch

of 1512 contains more material on wrestling than on swordplay, yet the

relationship between them is noticeable. The oldest known fencing text,

the late 13th century treatise MS I.33, even states, "For when one

will not cede to the other, but they press one against the other and

rush close, there is almost no use for arms, especially long ones, but

grappling begins, where each seeks to throw down the other or cast him

on the ground, and to harm and overcome him with many other means." But

just how all this heritage relates to the foyning fence of the Renaissance

is less well understood. This has been an area traditionally overlooked

by enthusiasts and it is understandable that many enthusiasts have come

to the wrong conclusions. The

skills of grappling and the art of wrestling have a long legacy in Europe.

In the early 1500s, many soldiers, scholars, priests, and nobles wrote

that wrestling was important in preparing aristocratic youth for military

service. The detailed depictions of unarmed techniques in many Medieval

fencing manuals (such as those by Fiore Dei Liberi and Hans Talhoffer)

are well known and accounts of wrestling and grappling abound in descriptions

of 15th century tournaments and judicial contests. A 1442 tournament

fight in Paris "with weapons as we are accustomed to carrying in

battle" included in its fourth article the stipulation "that

each of us may help each other with wrestling, using legs, feet, arms

or hands." English knightly tournaments as late as 1507 allowed

combatants "To Wrestle all maner of wayes" or to fight "with

Gripe, or otherwise". The Hispano-Italian master Pietro Monte in

the 1480’s even recognized wrestling as the "foundation of

all fighting", armed or unarmed. Albrecht Duerer’s Fechtbuch

of 1512 contains more material on wrestling than on swordplay, yet the

relationship between them is noticeable. The oldest known fencing text,

the late 13th century treatise MS I.33, even states, "For when one

will not cede to the other, but they press one against the other and

rush close, there is almost no use for arms, especially long ones, but

grappling begins, where each seeks to throw down the other or cast him

on the ground, and to harm and overcome him with many other means." But

just how all this heritage relates to the foyning fence of the Renaissance

is less well understood. This has been an area traditionally overlooked

by enthusiasts and it is understandable that many enthusiasts have come

to the wrong conclusions.

Nonetheless, all historical armed combat (Medieval and Renaissance,

cutting or thrusting) involved some degree of grappling and wrestling

techniques. But, as few Renaissance fencing manuals include detailed

sections on grappling and wrestling or even discuss seizures and disarms,

the popular view has been that they were not used or were viewed with

disdain. Besides, aren’t unarmed and pugilistic attacks merely

unskilled "thuggery" practiced only by the lower classes? After

all, surely one should not need to wrestle if one knows the sword "to

perfection"? (…and yet how many are "perfect" with

their sword, we might ask?). Nonetheless, all historical armed combat (Medieval and Renaissance,

cutting or thrusting) involved some degree of grappling and wrestling

techniques. But, as few Renaissance fencing manuals include detailed

sections on grappling and wrestling or even discuss seizures and disarms,

the popular view has been that they were not used or were viewed with

disdain. Besides, aren’t unarmed and pugilistic attacks merely

unskilled "thuggery" practiced only by the lower classes? After

all, surely one should not need to wrestle if one knows the sword "to

perfection"? (…and yet how many are "perfect" with

their sword, we might ask?).

This common view makes perfect sense, after all, as a slender cut-and-thrust

sword or rapier is a weapon whose characteristics are perfectly suited

to keeping an opponent off and killing him at range. Intentionally closing-in

to resort to hands-on brute strength would seem antithetical to the very

nature and advantage of the weapon. In actuality, the matter is that

such actions were not primitive, but advanced techniques that required

considerable practice and skill to execute –and knowing them could

make a fighter a more well-rounded and dangerous opponent in combat.

Yet, fencing historians have typically seen these advanced techniques

as being crudities and mere "tricks". Part of this prejudice

perhaps stems from the surviving 18th & 19th century view of swordplay

as being essentially that of personal "duel of honor" or gentlemanly

private quarrel. The traditional focus there has been on fencing as "blade

on blade" action rather than on "fighting" with swords

in battle or sudden urban assault. This was not the case in the 1500’s

and 1600’s. Armed fighting ranged from all manner of encounters

with all manner of bladed weapons. This common view makes perfect sense, after all, as a slender cut-and-thrust

sword or rapier is a weapon whose characteristics are perfectly suited

to keeping an opponent off and killing him at range. Intentionally closing-in

to resort to hands-on brute strength would seem antithetical to the very

nature and advantage of the weapon. In actuality, the matter is that

such actions were not primitive, but advanced techniques that required

considerable practice and skill to execute –and knowing them could

make a fighter a more well-rounded and dangerous opponent in combat.

Yet, fencing historians have typically seen these advanced techniques

as being crudities and mere "tricks". Part of this prejudice

perhaps stems from the surviving 18th & 19th century view of swordplay

as being essentially that of personal "duel of honor" or gentlemanly

private quarrel. The traditional focus there has been on fencing as "blade

on blade" action rather than on "fighting" with swords

in battle or sudden urban assault. This was not the case in the 1500’s

and 1600’s. Armed fighting ranged from all manner of encounters

with all manner of bladed weapons.

Yet, because approval of grappling and wrestling in the period was inconsistent

and often curtailed during fencing practice, understanding its true value

can be confusing now for students unfamiliar with either the actual evidence

or the actual techniques. In the early 1500’s the Italian solider-priest

Celio Calacagnini listed wrestling as an exercise required for preparing

upper-class youths for military service. In 1528, the courtier Baldassare

Castiglione wrote, " it is of the highest importance to know how

to wrestle, since this often accompanies combat on foot." In 1531

the English scholar and diplomat Sir Thomas Elyot wrote, "There

be divers maners of wrastlinges" and "undoubtedly it shall

be founde profitable in warres, in case that a capitayne shall be constrayned

to cope with his aduersary hande to hande, hauyng his weapon broken or

loste. Also it hath ben sene that the waiker persone, by the sleight

of wrastlyng, hath ouerthrowen the strenger, almost or he coulde fasten

on the other any violent stroke." In 1575, Michel de Montaigne,

the French Renaissance thinker, essayist, and courtier, wrote "our

very exercises and recreations, running, wrestling …and fencing".

In the notorious 1547 duel between the nobles Jarnac and Chastaignerai,

Jarnac was so concerned at Chastaignerai’s well known skill as

a wrestler (not to mention fencing) that to avoid the chance of a close

struggle, he insisted both parties each wear two daggers. Alfred Hutton’s

account from Vulson de la Colombière’s in 1549 of a judicial

combat between one D’aguerre and Fendilles states, "D’aguerre

let fall his sword, and being an expert wrestler (for be it understood

that no one in those days was considered a complete man-at-arms unless

he was proficient in the wrestling art), threw his enemy, held him down,

and, having disarmed him of his morion, dealt him many severe blows on

the head and face with it…". Yet, because approval of grappling and wrestling in the period was inconsistent

and often curtailed during fencing practice, understanding its true value

can be confusing now for students unfamiliar with either the actual evidence

or the actual techniques. In the early 1500’s the Italian solider-priest

Celio Calacagnini listed wrestling as an exercise required for preparing

upper-class youths for military service. In 1528, the courtier Baldassare

Castiglione wrote, " it is of the highest importance to know how

to wrestle, since this often accompanies combat on foot." In 1531

the English scholar and diplomat Sir Thomas Elyot wrote, "There

be divers maners of wrastlinges" and "undoubtedly it shall

be founde profitable in warres, in case that a capitayne shall be constrayned

to cope with his aduersary hande to hande, hauyng his weapon broken or

loste. Also it hath ben sene that the waiker persone, by the sleight

of wrastlyng, hath ouerthrowen the strenger, almost or he coulde fasten

on the other any violent stroke." In 1575, Michel de Montaigne,

the French Renaissance thinker, essayist, and courtier, wrote "our

very exercises and recreations, running, wrestling …and fencing".

In the notorious 1547 duel between the nobles Jarnac and Chastaignerai,

Jarnac was so concerned at Chastaignerai’s well known skill as

a wrestler (not to mention fencing) that to avoid the chance of a close

struggle, he insisted both parties each wear two daggers. Alfred Hutton’s

account from Vulson de la Colombière’s in 1549 of a judicial

combat between one D’aguerre and Fendilles states, "D’aguerre

let fall his sword, and being an expert wrestler (for be it understood

that no one in those days was considered a complete man-at-arms unless

he was proficient in the wrestling art), threw his enemy, held him down,

and, having disarmed him of his morion, dealt him many severe blows on

the head and face with it…".

A Ritterakedemie or "Knight’s School" was reportedly

set up in 1589 at Tübingen in Germany to instruct aristocratic youths

in skills which included wrestling, fencing, riding, dancing, tennis,

and firearms. Joachim Meyer offered significant elements of grappling

and wrestling with swords in his Fechtbuch of 1570 and in the 1580’s

the French general Francois de la Noue advocated wrestling in the curriculum

of military academies and the famed chronicler of duels, Brantome, also

tells us that wrestling was highly regarded at the French court. The

Bolognese master, Lelio de Tedeschi, even produced a manual on the art

of disarming in 1603. In 1625, Englishman Richard Peeke fought in a rapier

duel at Cadiz, defeating the Spaniard Tiago by sweeping his legs out

from under him after trapping his blade with his hilt. In 1617 Joseph

Swetnam commented on the value of skill in wrestling for staff fighting.

But as Dr. Anglo has pointed out, in 1622, Englishman Henry Peacham questioned

whether "throwing and wrestling" were more befitting common

soldiers rather than nobility, while his contemporary Lord Herbert of

Cherbury who studied martial arts in France, found them "qualities

of great use". At the turn of the 17th century in France, the celebrated

rapier duelists Lagarde and Bazanez came into conflict (the celebrated "duel

of the hat") and ended up on the ground violently stabbing and fighting

each other. A Ritterakedemie or "Knight’s School" was reportedly

set up in 1589 at Tübingen in Germany to instruct aristocratic youths

in skills which included wrestling, fencing, riding, dancing, tennis,

and firearms. Joachim Meyer offered significant elements of grappling

and wrestling with swords in his Fechtbuch of 1570 and in the 1580’s

the French general Francois de la Noue advocated wrestling in the curriculum

of military academies and the famed chronicler of duels, Brantome, also

tells us that wrestling was highly regarded at the French court. The

Bolognese master, Lelio de Tedeschi, even produced a manual on the art

of disarming in 1603. In 1625, Englishman Richard Peeke fought in a rapier

duel at Cadiz, defeating the Spaniard Tiago by sweeping his legs out

from under him after trapping his blade with his hilt. In 1617 Joseph

Swetnam commented on the value of skill in wrestling for staff fighting.

But as Dr. Anglo has pointed out, in 1622, Englishman Henry Peacham questioned

whether "throwing and wrestling" were more befitting common

soldiers rather than nobility, while his contemporary Lord Herbert of

Cherbury who studied martial arts in France, found them "qualities

of great use". At the turn of the 17th century in France, the celebrated

rapier duelists Lagarde and Bazanez came into conflict (the celebrated "duel

of the hat") and ended up on the ground violently stabbing and fighting

each other.

|

|

There is evidence close-in techniques were excluded from the German

Fechtschulen events of the 1500s where, in order to perform safe displays,

rules were in place to prevent such techniques. Similarly, the 1573 Sloane

manuscript of the London Masters of Defence states that in Prize Playing

events "who soever dothe play agaynst ye prizor, and doth strike

his blowe and close withall so that the prizor cannot strike his blowe

after agayne, shall Wynn no game for anny Veneye". The implication

in such cases is that while closing and seizing is effective and understood,

it is inappropriate for the public display intended to show a student’s

skill at defending and delivering blows. In 1579, Heinrich Von Gunterrodt

noted that "Fencing is a worthy, manly, and most noble Gymnastic

art, established by principles of nature…which serves both gladiator

and soldier, indeed everyone, in …battles, and single-combats,

with every hand-to-hand weapon, and also wrestling, for strongly defending,

and achieving victory over." Von Gunterrodt, also observed: in fencing, "when

one will not cede to the other, but they press one against the other

and rush close, there is almost no use for arms, especially long ones,

but grappling begins, where each seeks to throw down the other or cast

him on the ground, and to harm and overcome him with many other means." There is evidence close-in techniques were excluded from the German

Fechtschulen events of the 1500s where, in order to perform safe displays,

rules were in place to prevent such techniques. Similarly, the 1573 Sloane

manuscript of the London Masters of Defence states that in Prize Playing

events "who soever dothe play agaynst ye prizor, and doth strike

his blowe and close withall so that the prizor cannot strike his blowe

after agayne, shall Wynn no game for anny Veneye". The implication

in such cases is that while closing and seizing is effective and understood,

it is inappropriate for the public display intended to show a student’s

skill at defending and delivering blows. In 1579, Heinrich Von Gunterrodt

noted that "Fencing is a worthy, manly, and most noble Gymnastic

art, established by principles of nature…which serves both gladiator

and soldier, indeed everyone, in …battles, and single-combats,

with every hand-to-hand weapon, and also wrestling, for strongly defending,

and achieving victory over." Von Gunterrodt, also observed: in fencing, "when

one will not cede to the other, but they press one against the other

and rush close, there is almost no use for arms, especially long ones,

but grappling begins, where each seeks to throw down the other or cast

him on the ground, and to harm and overcome him with many other means."

George Silver’s views of 1599 advocating "gryps and seizures" in

swordplay are well known. Interestingly though, Silver lamented how such

things were no longer being taught by teachers of defence, saying "…there

are now in these dayes no gripes, closes, wrestlings, striking with the

hilts, daggers, or bucklers, used in Fence-schools". However, Silver

also describes situations which are quite familiar and reasonable to

those who today practice rapier fencing with more inclusive guidelines

for intentional close-contact. Silver, in his Paradoxes of Defence, section

31, actually complains that the rapier’s excessive length allows

for close-in fighting without much fear because there is little threat

to prevent it once the point is displaced. He writes: "Of the single

rapier fight between valiant men, having both skill, he that is the best

wrestler, or if neither of them can wrestle, the strongest man most commonly

kills the other, or leaves him at his mercy". He then describes

what happens typically when the fighters both rush together, explaining: George Silver’s views of 1599 advocating "gryps and seizures" in

swordplay are well known. Interestingly though, Silver lamented how such

things were no longer being taught by teachers of defence, saying "…there

are now in these dayes no gripes, closes, wrestlings, striking with the

hilts, daggers, or bucklers, used in Fence-schools". However, Silver

also describes situations which are quite familiar and reasonable to

those who today practice rapier fencing with more inclusive guidelines

for intentional close-contact. Silver, in his Paradoxes of Defence, section

31, actually complains that the rapier’s excessive length allows

for close-in fighting without much fear because there is little threat

to prevent it once the point is displaced. He writes: "Of the single

rapier fight between valiant men, having both skill, he that is the best

wrestler, or if neither of them can wrestle, the strongest man most commonly

kills the other, or leaves him at his mercy". He then describes

what happens typically when the fighters both rush together, explaining:

"When two valiant men of skill at single rapier do fight, one or

both of them most commonly standing upon their strength or skill in wrestling,

will presently seek to run into the close…But happening both of

one mind, they rather do bring themselves together. That being done,

no skill with rapiers avail, they presently grapple fast their hilts,

their wrists, arms, bodies or necks, as in …wrestling, or striving

together, they may best find for their advantages. Whereby it most

commonly false out, that he that is the best wrestler, or strongest

man (if neither

of them can wrestle) overcomes, wrestling by strength, or fine skill

in wrestling, the rapier from his adversary, or casting him from him,

wither to the ground, or to such distance, that he may by reason thereof,

use the edge or point of his rapier, to strike or thrust him, leaving

him dead or alive at his mercy."

In his section 34, Of the long single rapier, or rapier and poniard

fight between two unskillful men being valiant, Silver also observes:

"When two unskillful men (being valiant) shall fight with long

single rapiers, there is less danger in that kind of fight, by reason

of their distance in convenient length, weight, and unwieldiness,

than is with short rapiers, whereby it comes to pass, that what hurt

shall

happen to be done, if any with the edge or point of their rapiers

is done in a moment, and presently will grapple and wrestle together,

wherein

most commonly the strongest or best wrestler overcomes, and the like

fight falls out between them, at the long rapier and poniard, but

much more deadly, because instead of close and wresting, they fall

most commonly

to stabbing with their poniards."

Of course, some might argue Silver was not a "rapier master" and

so did not understand "proper" fencing. Regardless, he was

obviously an experience, highly skilled martial artist and expert swordsman

who had seen valid methods of rapier fighting in actual use. Then there

is the case of "Austin Bagger, a very tall gentleman of his hands,

not standing much upon his skill" who Silver describes as having

with his sword and buckler fought the "Italian teacher of offense",

Signior Rocco with his two hand sword. Silver relates how Bagger "presently

closed with him, and struck up his heels, and cut him over the breech,

and trod upon him, and most grievously hurt him under his feet." Which

means he charged forward, swept his legs out from under him, slashed

his rear, and then stomped on him a few times while he was down. Of course, some might argue Silver was not a "rapier master" and

so did not understand "proper" fencing. Regardless, he was

obviously an experience, highly skilled martial artist and expert swordsman

who had seen valid methods of rapier fighting in actual use. Then there

is the case of "Austin Bagger, a very tall gentleman of his hands,

not standing much upon his skill" who Silver describes as having

with his sword and buckler fought the "Italian teacher of offense",

Signior Rocco with his two hand sword. Silver relates how Bagger "presently

closed with him, and struck up his heels, and cut him over the breech,

and trod upon him, and most grievously hurt him under his feet." Which

means he charged forward, swept his legs out from under him, slashed

his rear, and then stomped on him a few times while he was down.

Hutton tells us how in the year 1626, the Marquis de Beuvron and Francois

de Montmorency, Comte de Boutteville, the notorious rabid duelist and

bully, fought a duel together in which both attacked "each other

so furiously that they soon come to such close quarters that their long

rapiers are useless. They throw them aside, and, grappling with one another,

attempt to bring their daggers into play." In 1671 an affray took

place in Montreal, Canada, between Lieutenant de Carion and Ensign de

Lormeau. While walking home with his wife, de Lormeau was confronted

by de Carion backed by two friends. Provoked into fighting by de Carion,

both men drew swords and exchanged blows. De Lormeau was wounded three

times, including wounds to the head and arm. Both wrestled briefly before

de Carion struck de Lormeau repeatedly on the head with his pommel. They

were then separated by some five passing onlookers and both combatants

survived. Hutton tells us how in the year 1626, the Marquis de Beuvron and Francois

de Montmorency, Comte de Boutteville, the notorious rabid duelist and

bully, fought a duel together in which both attacked "each other

so furiously that they soon come to such close quarters that their long

rapiers are useless. They throw them aside, and, grappling with one another,

attempt to bring their daggers into play." In 1671 an affray took

place in Montreal, Canada, between Lieutenant de Carion and Ensign de

Lormeau. While walking home with his wife, de Lormeau was confronted

by de Carion backed by two friends. Provoked into fighting by de Carion,

both men drew swords and exchanged blows. De Lormeau was wounded three

times, including wounds to the head and arm. Both wrestled briefly before

de Carion struck de Lormeau repeatedly on the head with his pommel. They

were then separated by some five passing onlookers and both combatants

survived.

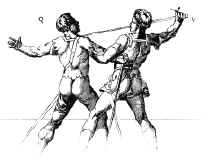

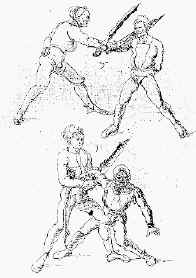

Closing in to strike, to grab, trip, throw, or push the opponent down

is seen in countless Renaissance fencing manuals from the cut-and-thrust

style swords of Marozzo in 1536 to the slender rapier of Giovanni Lovino

in 1580 and that of L'Lange in 1664. Jacob Wallhausen’s 1616 depictions

of military combat (armored and unarmored) show much the same. Dr. Sydney

Anglo calls this desperate armed or unarmed combat "all-in fighting" as

opposed to formal duels with rules, and describes it as: "one other

area of personal combat which was taught by masters throughout Europe,

and was practiced at every level of the social hierarchy whether the

antagonists were clad in defensive armor or not". He adds that, "Even

in Spain, where it might be thought that mathematical and philosophical

speculation had eliminated such sordid realities, wrestling tricks were

still taught by the masters –as well illustrated in early seventeenth-century

manuscripts treatises by Pedro de Heredia, cavalry captain and member

of the war council of the King of Spain". Heredia’s illustrations

of rapier include several effective close-in actions that hark back to

similar techniques of Marozzo and even Fiore Dei Liberi in 1410. Closing in to strike, to grab, trip, throw, or push the opponent down

is seen in countless Renaissance fencing manuals from the cut-and-thrust

style swords of Marozzo in 1536 to the slender rapier of Giovanni Lovino

in 1580 and that of L'Lange in 1664. Jacob Wallhausen’s 1616 depictions

of military combat (armored and unarmored) show much the same. Dr. Sydney

Anglo calls this desperate armed or unarmed combat "all-in fighting" as

opposed to formal duels with rules, and describes it as: "one other

area of personal combat which was taught by masters throughout Europe,

and was practiced at every level of the social hierarchy whether the

antagonists were clad in defensive armor or not". He adds that, "Even

in Spain, where it might be thought that mathematical and philosophical

speculation had eliminated such sordid realities, wrestling tricks were

still taught by the masters –as well illustrated in early seventeenth-century

manuscripts treatises by Pedro de Heredia, cavalry captain and member

of the war council of the King of Spain". Heredia’s illustrations

of rapier include several effective close-in actions that hark back to

similar techniques of Marozzo and even Fiore Dei Liberi in 1410.

The chronicler of duels, Brantome, tells us of a judicial duel in the

mid-1500’s wherein the Baron de Gueerres fought one Fendilles.

Having received a terrible thrust in the thigh, the Baron availed himself

of his wrestling skills and "closed with his antagonist and bore

him to the ground; and there the two lay and struggled". He also

relates a sword & dagger duel between the Spanish Captain Alonso

de Sotomayor and the knight Bayard. After some figting Sotomayor missed

a thrust which Bayard answered by deeply piercing his throat that he

could not withdraw his weapon. Sotomayor was still able to grapple with

Bayard so that both fell where Bayard then managed to stab Sotomayor

in the face with his dagger.

Some would still give us the impression today that personal combat in

the Renaissance consisted only of cavaliers and courtiers formally dueling

each other and apparrently no gentleman or courtier in the period ever

fought under any other condition or for any other reason other than affairs

of honor. Of course, it must be thoroughly understood that it was the

Renaissance aristocracy who were primarily recording accounts of duels

and frays and who naturally wrote almost exclusively about combats among

their own social class. Naturally, proper duels (illegal or not) were

far more interesting to them than everyday fights (by gentry or commoner)

which garnered neither reputation nor honor. But the actual evidence

from the period suggests a very different character than a conception

of simple "honorable" swordplay.

Continued in Part 2

About The Author:

John Clements is an authority on historical fencing and one of the world’s

foremost practitioners of Medieval and Renaissance fencing. He is a long-time

martial-artist who has been studying historical fencing since 1980. He

has practiced cut & thrust swordsmanship and rapier fighting for

more than eighteen years. John has researched swords and arms in 8 countries

and taught sword seminars in 6 countries. Since summer 1997 he has taught

public courses and private lessons in Houston. He has authored numerous

articles on swords and weapon fighting for several magazines including:

Renaissance Magazine, Tactical Knives, Karate International, Histoire'

Medievale, L’art de la Guerre, Master at Arms, The

Sword, Hammerterz

Forum, Hop-Lite, and Sword Forum International. John was also major contributor

on historical fencing as well as member of the editorial board to the

new Martial Arts of the World encyclopedia from ABC-CLIO Press (October

2001). He has also authored five books including: Medieval Swordsmanship:

Illustrated Methods & Techniques (Paladin Press, Nov ’98) and

Renaissance Swordsmanship: The Illustrated Use of Rapiers and Cut-and-Thrust

Swords (Paladin Press, March '97). John has also been featured twice

on The History Channel, and was the creator and a founding member of

the original Swordplay Symposium International. In 1982 he founded the

Medieval Battling Club. John is the Director of The Association

For Renaissance Martial Arts (ARMA), where this article was originally

featured.

|