Martial Arts: Japanese Archery

Kyudo: Way Of The Bow - Part 1

By Raymond A. Sosnowski, MS, MS, MA

Editor’s

Note: This

is a two part article on Japanese archery, or way of the bow, one

of the oldest

of Japan’s traditional martial arts. Kyudo is distinguished

by the fact that it is not practiced as sport, or as a modern self-defense

system that embodies a classical military tradition, but as a form

of spiritual practice associated with Zen. This article series will

provide the reader with an overview of this spiritual art. Part 1

of this series includes the Definition of the art, Principles & Concepts,

Techniques & Training, Methods, Etiquette & Customs and

Practice Clothing/Uniforms. Part 2 covers the related topics of

Equipment,

Equipment Care, Styles, Ranking, Training Facilities, History,

and a Bibliography. A glossary of terms will appear separately. |

(Courtesy Don Warrener)

|

Kyudo is written with the two kanji characters for “yumi” (bow)

and “michi” (way/path), but it is pronounced “kyudo” when

written together (it’s a quirk of the Japanese language), and,

therefore, it quite literally means the “way of the bow.” Kyudo

is derived from the Japanese military practice of kyujutsu (“art/science

of the bow,” that is, combat-style archery), and it is a “moving

meditation” like the Japanese cultural arts of shodo (“way

of the brush”) and chado (“way of tea”). It is a complementary

practice to zazen (seated meditation) as Kyudo is a form of ritsuzen

(standing meditation) [e.g., Herrigel (1953), and a critical review in

Yamada (2001)].

Kyudo is derived from the Japanese military practice of

kyujutsu, or combat-style archery depicted in this historic woodblock

print of a samurai using his bow while seated on a swimming hose. (Courtesy

of Christopher Caile) Kyudo is derived from the Japanese military practice of

kyujutsu, or combat-style archery depicted in this historic woodblock

print of a samurai using his bow while seated on a swimming hose. (Courtesy

of Christopher Caile)

Next to iaido (the way of Japanese sword drawing),

kyudo as an art of self-defense has no real practical uses. One is

not very

likely to use it for self-defense like karate-do, aikido (“way

of harmony”) or judo (the “gentle way”), nor even use

it for hunting. And yet, it is probably one of the most aesthetically

pleasing of all Japanese budo (martial ways), and it is one of the most

spiritual (Sosnowski, 2000); in this sense as well as visually, Kyudo

could be considered to be the Japanese analogue to the Chinese art of

T’ai Chi Ch’uan. Principles & Concepts

|

|

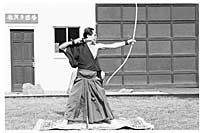

(Courtesy Dan and Jackie

DeProspero) (1)

|

A very basic principle in kyudo is “spirit, bow and body as one,” analogous

to “ki ken tai ichi” (“spirit, sword and body as one”)

in iaido and kendo (Japanese fencing). Instead of the uncoupled actions

of separate elements, all elements must act together as one in a coordinated

system in order to practice correctly. The ancient Chinese used ceremonial

archery to determine the quality of a man’s character (Selby, 2000),

and this idea was eventually incorporated into Japanese-style archery.

The state of mind is reflected in the attitude, form and the shot itself.

Initially “hitting the target” is relatively unimportant.

For those who practice kyudo solely as a meditation, this is always true

at face value; otherwise, it is like a koan (an illogical problem in

Zen). For all kyudo-ka (kyudo practitioners), it is a lesson in letting

go of the idea of “hitting the target;” when the baggage

of desire [“I WANT to hit the target”] is abandoned, then

through right form, the target can be hit consistently with ease. After

all, if the target really were unimportant, then there would be no purpose

in having a target at all. The actual emphasis on “hitting the

target” is specific to the individual ryuha (styles/schools and

their branches), and also depends on the individual kyudo-ka’s

developmental stage within the specific ryuha.

Many aspects for good budo practices are also present in kyudo including

metsuke (gaze), kokyo (breath), ikiai (harmony of breath), kamae (posture)

and hara (“belly” synonymous with centering and groundedness).

The aspect of “ma” (distance/timing) is also present; for

kyudo, ma is timing (considering that distance to the target is fixed),

governing the execution of proper movement. Finally, there are the various

balances: tenchi (heaven [and] earth) is the vertical balance along with

the complementary characteristics of upper and lower (supple and firm,

respectively), and migi-hidare (right-left) is the horizontal balance

in line with the mato (target). The vertical balance takes into account

gravity in the same way for a tree: the lower part, the roots and trunk,

are stable and provide the base; the upper part, the branches, are flexible

while maintaining their form and function. Both types of balance, horizontal

and vertical, have both static and dynamic manifestations.

Training

|

A historic woodblock print showing

a student practicing before his teacher. (Courtesy Christopher

Caile) |

In kyudo, as in many other budo, there are three basic

types of training: regular, individual (case-by-case), and gasshuku (intensive/seminar). “Regular

training” sessions, usually meet once or perhaps twice a week at

the same time and place; this is sometimes referred to as “formal” training,

and includes instruction and practice (some schools will include a zen

session as well). For those who practice outside of regular training,

there is “individual training,” and practicing alone fits

into this category; small groups may get together occasionally, and an

instructor may or may not be present – this is also referred to

as“informal” training. Finally, there is the “gasshuku,” a

gathering of members from different kyudojo (dojo or “practice

place” for kyudo), for concentrated practice and instruction; these

events can be from one to ten days long. For groups affiliated with the

All Nippon Kyudo Federation (ANKF), this is also a time for the taikai

(tournaments) and shinsa (promotion examinations).

Techniques & Training Methods

The kihon (basic techniques) are practiced in a kind of kihon-no-kata

(basic form); the ANKF refers to this kata as “hassetsu” (the

eight stages of shooting), whereas some lineages of Heki Ryu [refer to

STYLES below] retain the older term “shichido” (seven ways

or coordinations). These waza (techniques), in order of execution, are:

1. ashi-bumi - stepping out to position the feet and establish a stable

base.

2. do-zukuri - repositioning the body and the yumi, and then nocking

the ya (arrow).

3. yumi-gamae – engaging the tsuru (bowstring) with

the kake (shooting glove).

4. uchi-okoshi - raising the yumi.

5. hiki-wake in hassetsu; hiki-tori in

shichido - drawing the yumi.

6. kai (literally “meeting”) – pause

at full draw.

7. hanare - release.

8. zanshin - lingering mind and body.

|

Kanjuro Shibata (c. 1990) in

Kai at the Ryuko Kyudojo in Boulder, CO. (Courtesy Zenko

International)

|

In shichido, the final two waza are counted together (zanshin is considered

a continuation of hanare) rather than separately. In essence, hassetsu

and shichido refer to the same set of kihon.

Although beginners can be trained individually, it is common to have

group training for beginners. Beginners concentrate on the kihon (basics).

Initially the beginner is without a kake (also referred to as a yugake),

just a yumi and ya, getting the feel of them. The ya is dropped off before

the drawing step; you go through the motion of drawing without drawing,

and through the motion of release without an actual release [one should

NEVER draw and release a real yumi without a ya - the yumi could be damaged].

Surgical tubing attached to a wooden handle (affectionately referred

to as “baby yumi” in some circles) is used to simulate the

stresses of drawing and releasing on the hands; the wooden handle is

held in the left hand, and the right hand pulls the tubing back in a

drawing motion. Then one puts on the kake and runs through the basic

sequence again, this time integrating the feel of using the kake into

the kihon. When the instructor determines that the beginner has got the

kihon down well enough, then a full draw and release are allowed at the

makiwara (short-distance target); this practice of short-distance shooting

is explained below.

Group instruction can be used for experienced students, but only to

instruct the overall form of the kata. Individual mentoring of experienced

students is required; corrections and fine-tuning are highly individualized

for the most part. Another aspect is visual learning or “stealing

with the eyes,” which is Japanese custom; Westerners tend to be

overly verbal, and, as such, are prone to asking too many questions and

demanding answers that they are usually not ready to hear. Given the

nature of kyudo, visual learning is not very difficult after a little

practice.

To train for form, especially in confined spaces, there is short-distance

shooting at the makiwara; traditionally round straw butts are used in

Japan, while hay or straw bales (sometimes wrapped in a sheet) are common

in the West (other materials such as styrofoam and rolls of corrugated

cardboard have been used as satisfactory substitutes). The makiwara is

on a stand at head height for standing shots. The kyudo-ka stands one

yumi-length away relative to the centerline of the body. The kihon-no-kata,

and any forms with a standing shooting position are practiced at the

makiwara; kneeling forms can be practiced at a makiwara on an appropriately

low stand.

Shooting is general done in a group setting, although the timing of

the sequence is individual. For even-numbered groups, there are also

various types of group shooting, including synchronized (all together),

sequential (singly or in synchronized pairs), and alternating synchronized

(people in odd-numbered positions are synchronized, as are the people

in the even-numbered positions; the two subgroups shoot sequentially);

the lead person in the first position sets the pace for the entire group.

Group shooting helps to bring one’s skill level up.

Etiquette & Customs

A pair of female Kyudo-ka, doing alternate shooting in

Hitote from the shooting platform at Seiko Kyudojo, Karme-Choling, Barnet,

VT, in June 2000. The standing Kyudo-ka is in Kai. (Courtesy of the

author) A pair of female Kyudo-ka, doing alternate shooting in

Hitote from the shooting platform at Seiko Kyudojo, Karme-Choling, Barnet,

VT, in June 2000. The standing Kyudo-ka is in Kai. (Courtesy of the

author)

The one word most often identified with kyudo is “dignified” -

every aspect is done with dignity. Another closely associated term is “courtesy.” So

it is not too surprising that the two types of rei (bows), tachi-rei

(standing bow) and za-rei (seated bow), are part of the initial lessons

in kyudo. Similarly, there is special consideration given to the instruction

of ashi-sabaki (foot work) in order to maintain dignified movement.

For practical reasons, there is a set of customs for shooting while

wearing a kimono because the left sleeve will get in the way of shooting

if not taken care of. The method for handling this problem is gender-specific.

Men perform hadanaugi-dosa, removing the left arm from the sleeve in

order to shoot with a bare left arm and shoulder; when finished, men

perform hadaire-dosa, replacing the left arm into the sleeve. Women,

on the other hand, perform tasuki-sabaki (cord motion); the kimono sleeves

are tied up with a cord or sash (O’Brian and Hartman, 1998).

Apart from the kihon, there is an additional set of kata that is practiced;

these are the koryu (classical style) forms. The ANKF has created a series

of “standardized” forms based on koryu kata, referring to

them collectively as “ceremonial shooting” (O’Brien,

1994). We can classify the koryu kata as standard, formal and special.

Kanjuro Shibata in his 20s in his Kyudojo Kanjuro Shibata in his 20s in his Kyudojo

in Kyoto; the posture is Sumashi

(addressing the target) in the form

called

Hitote.

(Courtesy Zenko

International)

There are three types of “standard forms” based on kneeling

or standing during the preparation work (getting to the point of having

the ya nocked) and on kneeling or standing during the actual shooting

(aligning the body, and then raising, drawing and releasing): (1) standing

during both the preparation and shooting, (2) kneeling during the preparation

and standing during shooting, and (3) kneeling during both the preparation

and shooting. The details vary among the various groups. “Formal

shooting,” usually referred to as reisha or sharei, is a variation

of the type-2 standard form, and has either one or two kaizoe (attendants);

again details vary among the various groups. Finally, there are the “special

forms,” which vary considerably among the different groups in terms

of number and use. For example, some ryuha have one or more funeral forms,

which are performed after the death of a headmaster, senior instructor,

an influential kyudo-ka (for example, see Sosnowski, 1999a), or a close

family member. Heki Ryu Chikurin-ha Kyudo also retains several special

forms from its kyujutsu origins, including a kneeling form referred to

as “castle shooting” in which the archer shoots up in a near

vertical trajectory, which comes from a medieval Japanese siege technique

of lobbing arrows over a castle wall, in order to land in a designated

circular area on the ground.

Practice Clothing/Uniforms

The

author, almost in Kai, at the DC Sakura Matsuri (Cherry Blossom Festival)

Kyudo demonstration by Miyako Kyudojo of Silver Spring,

MD, on 30 March 2002. This was part of a three-person sequential-shooting

ceremonial form called San-nin Reisha. (Courtesy Ramona Matthews) The

author, almost in Kai, at the DC Sakura Matsuri (Cherry Blossom Festival)

Kyudo demonstration by Miyako Kyudojo of Silver Spring,

MD, on 30 March 2002. This was part of a three-person sequential-shooting

ceremonial form called San-nin Reisha. (Courtesy Ramona Matthews)

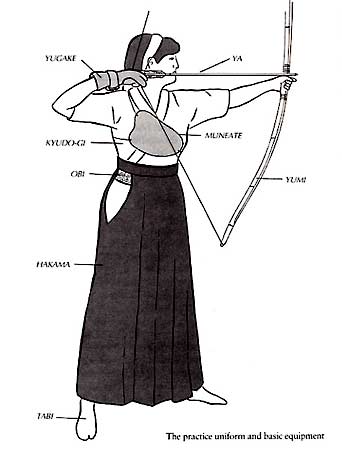

The level of practice/training determines what is worn. For informal

practice and beginner training, regular street clothes, provided that

they are clean and comfortable, but neither too loose nor too tight,

are worn. For regular practice, one generally wears a keiko-gi (a white,

short-sleeved top), an obi (a wide, thin belt, more like an iaido belt

rather than a karate belt, which is narrow and thick), a dark blue or

black hakama (wide-legged pleated trousers; women traditionally wear

a skirt that is an undivided hakama), and white tabi (split-toed socks).

Some groups specify that after a certain rank, senior practitioners wear

a kimono instead of a keiko-gi; other groups specify wearing kimono (or

equivalent) only for embu (formal demonstrations).

|

(Courtesy Kodansha International)

(2)

|

For embu, kimono are worn, although men may instead wear

montsuki (modified black “kimono,” which extend down only

to the mid-thigh level, with the mon or family crest on the front and

back of the sleeves and

the backs). The hakama can be a solid (but not loud) color; men generally

wear formal hakama with a two- or three-tone stripe pattern. Recall that

while shooting, women will have their kimono sleeves tied up (tasuki-sabaki),

and men will bare their left arm by slipping it out of the sleeve (hadanaugi-dosa).

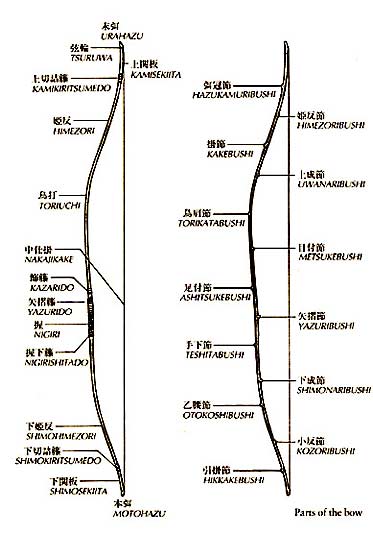

The most expensive purchase is the yumi, which is a recurved, asymmetric

long bow of laminated construction. A yumi is “recurved” because,

when unstrung, its shape is the reverse of that when strung. It is “asymmetric” because

the nigiri (grip) separates the lower third from the upper two-thirds

(see Koppedrayer, 1995), and there is also a slight right-left asymmetry

as well. It is a “long bow” because its length exceeds the

height of the archer. A traditional yumi has a laminated cross section

- the facings are madake (Japanese timber bamboo) while the core and

side strips along with the sekiita (end-plates onto which the end loops

of the tsuru are attached) are hardwood; functional yumi “replica” are

made of synthetic materials like fiberglass and carbon-fiber.

|

In

modern Kyudo three types of bows (yumi) are used: the standard

bamboo yumi, lacquered bamboo yumi, and synthetic yumi (fiberglass

or carbon) that are most often used by Kyudo schools or clubs

because of their durability. Generally, however, most traditional

practitioners prefer the non-synthetic yumi which is esthetically

parallels the essence of the practice. (Courtesy Kodansha

International) (3)

|

The size and draw strength of the yumi

are fit to the individual. The standard length of a yumi is 221 cm (87

in) based on the average

Japanese

height of 150-165 cm (59-65 in). To accommodate taller practitioners,

there are four additional lengths (6 cm [2.4 in] increments in length

for each additional 15 cm [5.9 in] in height). The draw strength varies

by gender, age, and experience. For beginners, an adult female typically

has an 8 to 14 Kg (17.6 to 30.8 lb) draw strength, while a male is between

10 and 15 Kg (22 and 33 lb). Within a year, with regular practice, practitioners

will need a stronger yumi - it is a good idea to use class yumi for the

first year for this reason. Females will average between 14 and 16 Kg

(30.8 and 35.2 lb), and males between 18 and 20 Kg (39.6 and 44 lb).

Depending on the individual, several changes in strength may be needed

over the course of many years. Yumi are typically made up to about 30

Kg (66 lb); it is the rare individual who needs one stronger. As one

ages, there comes a time when the yumi becomes too strong and one cuts

back on the draw strength. The draw strength should be sufficient to

be on the edge of a challenge (the “Goldilocks” principle

- not too much and not too little, but just right).

The size and draw strength of the yumi are fit to the individual. The

standard length of a yumi is 221 cm (87 in) based on the average Japanese

height of 150-165 cm (59-65 in). To accommodate taller practitioners,

there are four additional lengths (6 cm [2.4 in] increments in length

for each additional 15 cm [5.9 in] in height). The draw strength varies

by gender, age, and experience. For beginners, an adult female typically

has an 8 to 14 Kg (17.6 to 30.8 lb) draw strength, while a male is between

10 and 15 Kg (22 and 33 lb). Within a year, with regular practice, practitioners

will need a stronger yumi - it is a good idea to use class yumi for the

first year for this reason. Females will average between 14 and 16 Kg

(30.8 and 35.2 lb), and males between 18 and 20 Kg (39.6 and 44 lb).

Depending on the individual, several changes in strength may be needed

over the course of many years. Yumi are typically made up to about 30

Kg (66 lb); it is the rare individual who needs one stronger. As one

ages, there comes a time when the yumi becomes too strong and one cuts

back on the draw strength. The draw strength should be sufficient to

be on the edge of a challenge (the “Goldilocks” principle

- not too much and not too little, but just right).

Along with the yumi, there is the tsuru (bowstring). Just as yumi are

made in prescribed lengths, there are associated length tsuru. Traditionally,

tsuru are made of hemp; these days there are also Kevlar and hemp-Kevlar

tsuru. Hemp tsuru are generally used by experienced kyudo-ka; they require

a lot of preparation work, and are not very durable. The hemp-Kevlar

tsuru is a welcome compromise between traditional material, and ease

of handling along with good durability. One unavoidable fact is that

tsuru break, generally while shooting - the yumi should be closely inspected

after this to be sure that there is no damage, and generally there is

none; one should always carry at least one spare tsuru for this reason.

There are several ways to protect yumi in transit. Simplest is a slipcover,

a very long narrow cloth bag that the yumi fits into. There is also a

wrapper, a length of cloth in a strip, usually with a design, print,

or even calligraphy on it, having a pocket at one end that is placed

over the upper sekiita; this strip is lag-wrapped around the yumi and

secured at the lower end by tying it with the attached himo. In order

to keep yumi dry in inclement weather, there is a rain cover - a plastic

slipcover that will hold several yumi. For airline, bus or train travel,

there are no carriers that I know of. Many people use very thin plywood

strips to cover the faces of the yumi, add a layer of bubble wrap, and

secure it with duct tape. Although it is possible to use PVC pipe or

PVC fishing rod carriers, the rise height of unstrung yumi are usually

too high for the available carriers, and require the use of wide diameter

pipes that are unwieldy to handle. One should not try to force a yumi

into a container that is not wide enough to handle it; it is not good

for the yumi to be forced out of shape because shape is everything for

the yumi to operate properly.

Yumi, being made of organic material under stress, have a finite lifetime.

Every yumi has a life cycle, which can be seen in the rise height, the

distance between the grip and a line between the two sekiita on an unstrung

yumi; this can be readily seen by placing the unstrung yumi on the floor,

and then rotating the yumi so that it is perpendicular to the floor with

the sekiita still on the floor. New yumi have a rather high rise height

of two to three fists. To tame a new yumi, it is generally left strung

between four and twelve weeks as necessary to bring the rise height down

a bit. In a mature yumi, the rise height is between one and two fists;

it is only strung when in use, although for programs of three to ten

days they can usually remain strung for the duration if it is used every

day. An old yumi becomes “tired” through the loss of elasticity,

and has a rise height of no more than one fist. An old yumi should be

used seldom, and eventually it should be retired from use. Yumi can also

break – excessive dryness is the usual cause; sometimes they can

be repaired and other times they cannot.

|

At right in the background is a makiwara (target) using

a hay bale: Kyudo demonstration at 2000 Cherry Blossom Festival in

Brooklyn, NY. (Courtesy Christopher Caile) |

A wooden barrel stuffed with straw is used as a makiwara

as seen in this historic woodblock print from the 1870s. (Courtesy

of Christopher Caile) |

|

For short distance shooting at one bow-length away, a makiwara is used

as a target. Traditionally, it is a drum of straw on a stand. It is common

here to use straw or hay bales wrapped in a white sheet to make handling

and transport a little neater. Generally, a kyudojo will have several

on stands or holders set at varying heights to accommodate the various

statures of different practitioners. It is not uncommon for individuals

to set one up at home, either indoors or outdoors as space permits, for

their own practice.

For distance shooting, a number of mato are set up; some groups use

an odd number (resulting in more than one person per mato) while other

groups use one per archer. For standard 28 m (91.9 ft) courses, a 36

cm (14.2 in) diameter mato is used. The mato is a cylindrical wood frame

with a paper face, which is the target face; hoshi-mato have a single

black center spot, while kasumi-mato have three concentric black rings

about a white center (the outer ring goes to the rim of the target).

Use varies by school - one for regular practice and the other for special

occasions. A few individuals who have the space can set up outdoor, distance

shooting ranges. Many special programs set up temporary shooting areas

with a backstop of hay/straw bales [if possible and available, an arrow

net is set up just behind the target(s)]; otherwise, one is shooting

at a regular kyudojo (see TRAINING FACILITIES below).

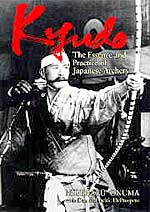

Kyudo: The Essence and Practice of Japanese Archery

is available from the FightingArts Estore:

(160 p., 7½ x 10½"

hardbound., fully illustrated)

US$32.95

(+$5 shipping within US)

About The Author:

Raymond Sosnowski began his martial arts training in 1973

at the Stevens [Tech] Karate Club in "Korean Karate," which

was then a euphemism for Tae Kwon Do; he trained for over sixteen years

in the ITF (International Taekwondo Federation) style, teaching for the

majority of that time. He has practiced Kuang P'ing Yang style T'ai-Chi

Ch'uan for twelve years beginning in 1987, and taught for several years,

giving several local seminars. His first weapons were the T'ai-Chi [straight]

sword and the Chinese iron fan. He came to the Japanese martial arts

in 1991, initially training in Aikido, first Shodokan (Tomiki-Ryu) and

then Aikikai style, and Aikido weapons (aiki-ken and aiki-jo). Training

in Japanese weapons began in 1996 with Iaido, Jodo, Kendo and Naginata;

Kyudo was added in 1997. He is a yudansha (or equivalent) in all these

arts, as well as an assistant instructor of Kyudo, and an instructor

of Iaido and Naginata. The study of Nakamura Ryu (along with Toyama Ryu)

Batto-do was added in 2003. He is also a student of Zen and the Shakuhachi

("Zen flute"). Sosnowski was a co-founder (1998) and the first

Secretary of the East Coast Naginata Federation as well as the principal

author of their by-laws. He was a co-director of the Guelph [Ontario]

School of Japanese Sword Arts (GSJSA) in 1998, 1999 and 2000, and made

presentations at the panel discussions during the GSJSA in 1999 and 2000.

In addition, he was a contributing author of articles, book reviews and

seminar reports to the now-defunct publications "The Iaido Newsletter" (TIN),

and "Journal of Japanese Sword Arts" (JJSA), in addition to "Ryubi

-- The Dragon's Tail (the newsletter of Kashima Shinryu/North America)." Current

and revised writings appear in "The Iaido Journal" section

of EJMAS (Electronic Journals of Martial Arts and Sciences) at <http://ejmas.com>.

He is an occasional contributor to Iaido-L, e-Budo, the Kendo World forums

and Sword Forum International. In his professional career, Mr. Sosnowski

is an Engineering Fellow and Technical Director of Maryland Technical

Center for Sonetech Corporation (with headquarters in Bedford, NH), specializing

in artificial intelligence methodologies and computer-based numerical

analyses, as well as being an expert in all phases of software development

including government documentation. He holds three masters degrees, [Physical]

Oceanography from the University of Connecticut (Storrs, CT), [Applied]

Mathematics from Rivier College (Nashua, NH), and Cognitive and Neural

Systems from Boston University, as well as a Bachelors in Physics from

the Stevens Institute of Technology (Hoboken, NJ). He lives with his

wife Valerie in rural Maryland between Washington, DC, and Baltimore,

MD, described by a friend as "a little piece of southern New Hampshire

in Maryland."

|