Kyudo: Way Of The Bow - Part 2

By Raymond A. Sosnowski, MS, MS, MA

Editor’s Note: This is the second of a two part article on Japanese

archery, or way of the bow, one of the oldest of Japan’s traditional

martial arts. Kyudo is distinguished by the fact that it is not practiced

as sport, or as a modern self-defense system that embodies a classical

military tradition, but as a form of spiritual practice associated with

Zen. Part

1 of this series included the Definition of the art, Principles & Concepts,

Techniques & Training, Methods, Etiquette & Customs and Practice

Clothing/Uniforms. Part 2 covers the related topics of Equipment, Equipment

Care, Styles, Ranking, Training Facilities, History, and a Bibliography.

A glossary of terms will appear separately.

Equipment

Unlike many other martial practices, kyudo has a lot of gear associated

with it. As such, it makes the practice somewhat costly. Many kyudojo

have class equipment to lend to practitioners, especially beginners.

Students can acquire equipment piece by piece, rather than having to

buy it all at once. It is also possible to obtain used equipment rather

than new as a way to keep costs down.

|

(Courtesy of Dan and Jackie

Deprospero)(1)

|

The first piece of personal equipment to acquire is generally the kake

(aka yugake). The design of the shooting glove dates back to the last

quarter of the 15th century. For standard shooting (makiwara and 28 m

[91.9 ft] distance), we use a three-fingered glove (mitsugake) made of

deerskin leather with a horn or wood thumb insert. By contrast, the five-fingered

glove is favored in yabusame (horseback archery), and the four-finger

glove is favored for extra-long distance (60 m [196.9 ft] or greater)

and endurance (12- or 24-hour) shooting. There is a ridge in the thumb

piece between the thumb and the index finger called the tsuru-makura

(the groove is called the tsuru-michi) - the tsuru is drawn with this

ridge, which is derived from the thumb ring from Mongolia and China.

The kake has a long himo (strap) at the wrist, which is wound around

the glove at the wrist to secure the kake; the method of tying the himo

depends on the ryuha. A cotton glove liner is worn with the glove. One

generally has a kake bag of sorts to carry the kake and liners in.

Optionally, there is an oshide-gake, a glove for the thumb of the left

hand. There are two types commonly available: the first is a simple thumb

cover with a thin himo to secure it to the wrist, and the second is glove

similar to the kake with a long himo wound several times around the glove

at the wrist. The latter type is also worn with a glove liner. The purpose

of the oshide-gake is to protect the top of the left thumb from being

lacerated by the fletching of a released ya.

(Courtesy of Kodansha International)(2)

(Courtesy of Kodansha International)(3)

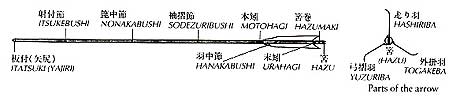

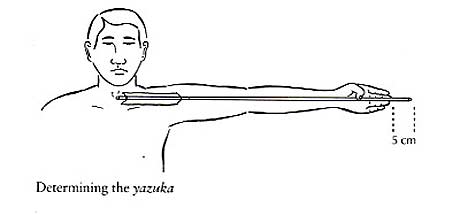

In general, the next piece of personal equipment acquired are a set

of ya (arrows). The length of the arrows for kyudo depends on one’s

draw - the metric is from the center of the throat to the tip of the

middle finger of the outstretched left arm plus three fingers (wide).

The longest standard ya available is about 103 cm (40.6 in) long; they

can be cut down to accommodate shorter draws [it is possible to special

order longer ya, but this is more expensive]. The shaft is traditionally

made of bamboo, although aluminum and carbon fiber have been used in

recent times.

|

(Courtesy of Dan and Jackie DeProspero) (4) |

|

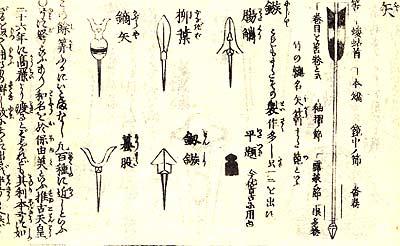

Samurai used a wide variety

of arrow tips a few of which are illustrated in this old woodblock

print image. (Courtesy of Christopher Caile) |

Ya come in two basic varieties, boya (unfletched) for makiwara shooting,

and kazuya (fletched) for distance shooting. [There are fletched ya for

makiwara shooting but the fletching tapers back to the shaft at the nock

end.] They also differ in their yanone (tips or points); these tips reflect

the strength of the targets to be penetrated (see below). The boya have

bullet-shaped or shallow cone-shaped metal points, which are metal caps

pressed onto the ends of the shafts; they need to penetrate the makiwara.

Kazuya have target-points (a very small cone raised at the tip of a shallow

cone); they need to pierce a taut paper target and the damp sand behind

it.

Hane (feathers) for the kazuya traditionally came from large raptors

(birds of prey), but in these days of endangered species and associated

international agreements, turkey and goose feathers are commonly used

instead. Kazuya come in pairs, the haya (first arrow) and otoya (second

arrow), and are shot in that order. When viewed from behind, haya rotate

clockwise, and otoya counterclockwise. The groove of the hazu (nock)

is aligned with one of the three fletchings, which is the top or cutting

feather. These days the hazu are plastic pieces that are inserted into

the end of the shaft; traditionally they are made of horn.

|

(Courtesy of Dan and

Jackie DeProspero) (5)

|

A case for ya, especially kazuya, is a must. Ideally, a case is

a bit wider at the upper end to accommodate the fletching. Long

canisters with straps for carrying rolled-up blueprints are a common

substitute as are appropriate length cardboard mailing tubes. At

the practice sites, it is common to have a ya box, a tall wooden

box with compartments, which hold the ya vertically without touching

the fletching.

At a minimum, one has one boya and a pair of kazuya. For practical

reasons, a pair of boya (in order to practice two ya style shooting

at the makiwara), and two pair of kazuya (to minimize waiting during

distance shooting) are recommended. Serious practitioners also

have at least one spare boya and one spare pair of kazuya, in case

any of the the ya that they are using are either damaged or lost,

that is, a total of at least three boya and three pairs of kazuya.

The most expensive purchase is the yumi, which is a recurved,

asymmetric long bow of laminated construction. A yumi is “recurved” because,

when unstrung, its shape is the reverse of that when strung. It

is “asymmetric” because the nigiri (grip) separates

the lower third from the upper two-thirds (see Koppedrayer, 1995),

and there is also a slight right-left asymmetry as well. It is

a “long bow” because its length exceeds the height

of the archer. A traditional yumi has a laminated cross section

- the facings are madake (Japanese timber bamboo) while the core

and side strips along with the sekiita (end-plates onto which the

end loops of the tsuru are attached) are hardwood; functional yumi “replica” are

made of synthetic materials like fiberglass and carbon-fiber. |

|

Kanjuro Shibata in his 20s in his Yumi workshop in Kyoto. (Courtesy

of Zenko International) |

The size and draw strength of the yumi are fit to the individual. The

standard length of a yumi is 221 cm (87 in) based on the average Japanese

height of 150-165 cm (59-65 in). To accommodate taller practitioners,

there are four additional lengths (6 cm [2.4 in] increments in length

for each additional 15 cm [5.9 in] in height). The draw strength varies

by gender, age, and experience. For beginners, an adult female typically

has an 8 to 14 Kg (17.6 to 30.8 lb) draw strength, while a male is between

10 and 15 Kg (22 and 33 lb). Within a year, with regular practice, practitioners

will need a stronger yumi - it is a good idea to use class yumi for the

first year for this reason. Females will average between 14 and 16 Kg

(30.8 and 35.2 lb), and males between 18 and 20 Kg (39.6 and 44 lb).

Depending on the individual, several changes in strength may be needed

over the course of many years. Yumi are typically made up to about 30

Kg (66 lb); it is the rare individual who needs one stronger. As one

ages, there comes a time when the yumi becomes too strong and one cuts

back on the draw strength. The draw strength should be sufficient to

be on the edge of a challenge (the “Goldilocks” principle

- not too much and not too little, but just right).

Along with the yumi, there is the tsuru (bow string). Just as yumi are

made in prescribed lengths, there are associated length tsuru. Traditionally,

tsuru are made of hemp; these days there are also Kevlar and hemp-Kevlar

tsuru. Hemp tsuru are generally used by experienced kyudo-ka; they require

a lot of preparation work, and are not very durable. The hemp-Kevlar

tsuru is a welcome compromise between traditional material, and ease

of handling along with good durability. One unavoidable fact is that

tsuru break, generally while shooting - the yumi should be closely inspected

after this to be sure that there is no damage, and generally there is

none; one should always carry at least one spare tsuru for this reason.

There are several ways to protect yumi in transit. Simplest is a slipcover,

a very long narrow cloth bag that the yumi fits into. There is also a

wrapper, a length of cloth in a strip, usually with a design, print,

or even calligraphy on it, having a pocket at one end that is placed

over the upper sekiita; this strip is lag-wrapped around the yumi and

secured at the lower end by tying it with the attached himo. In order

to keep yumi dry in inclement weather, there is a rain cover - a plastic

slipcover that will hold several yumi. For airline, bus or train travel,

there are no carriers that I know of. Many people use very thin plywood

strips to cover the faces of the yumi, add a layer of bubble wrap, and

secure it with duct tape. Although it is possible to use PVC pipe or

PVC fishing rod carriers, the rise height of unstrung yumi are usually

too high for the available carriers, and require the use of wide diameter

pipes that are unwieldy to handle. One should not try to force a yumi

into a container that is not wide enough to handle it; it is not good

for the yumi to be forced out of shape because shape is everything for

the yumi to operate properly.

Yumi, being made of organic material under stress, have a finite lifetime.

Every yumi has a life cycle, which can be seen in the rise height, the

distance between the grip and a line between the two sekiita on an unstrung

yumi; this can be readily seen by placing the unstrung yumi on the floor,

and then rotating the yumi so that it is perpendicular to the floor with

the sekiita still on the floor. New yumi have a rather high rise height

of two to three fists. To tame a new yumi, it is generally left strung

between four and twelve weeks as necessary to bring the rise height down

a bit. In a mature yumi, the rise height is between one and two fists;

it is only strung when in use, although for programs of three to ten

days they can usually remain strung for the duration if it is used every

day. An old yumi becomes “tired” through the loss of elasticity,

and has a rise height of no more than one fist. An old yumi should be

used seldom, and eventually it should be retired from use. Yumi can also

break – excessive dryness is the usual cause; sometimes they can

be repaired and other times they cannot.

For short distance shooting at one bow-length away, a makiwara is used

as a target. Traditionally, it is a drum of straw on a stand. It is common

here to use straw or hay bales wrapped in a white sheet to make handling

and transport a little neater. Generally, a kyudojo will have several

on stands or holders set at varying heights to accommodate the various

statures of different practitioners. It is not uncommon for individuals

to set one up at home, either indoors or outdoors as space permits, for

their own practice.

|

(Courtesy of Deborah Klens-Bigman) |

For distance shooting, a number of mato are set up; some groups use

an odd number (resulting in more than one person per mato) while other

groups use one per archer. For standard 28 m (91.9 ft) courses, a 36

cm (14.2 in) diameter mato is used. The mato is a cylindrical wood frame

with a paper face, which is the target face; hoshi-mato have a single

black center spot, while kasumi-mato have three concentric black rings

about a white center (the outer ring goes to the rim of the target).

Use varies by school - one for regular practice and the other for special

occasions. A few individuals who have the space can set up outdoor, distance

shooting ranges. Many special programs set up temporary shooting areas

with a backstop of hay/straw bales [if possible and available, an arrow

net is set up just behind the target(s)]; otherwise, one is shooting

at a regular kyudojo (see TRAINING FACILITIES below).

Equipment Care

Since most of the equipment used is made of organic material, a number

of common sense care practices are in order. Ya are stored vertically;

yumi are stored either horizontally or vertically. For both, avoid extremes

of temperature and humidity. Check them for cracks; check the yumi for

shape and alignment when strung. Attend to any minor repairs immediately;

seek qualified repair services for any major repair work. Don’t

use equipment that needs repair, especially yumi. Dry the kake and liners

when they have absorbed perspiration; wash the liners. It is a good idea

to have several liners (so there is no problem if one is misplaced, and

to provide extras over a long training program).

In order to make minor repairs, one should have a personal equipment

repair bag. First, one needs to carries spare tsuru, hazu and both types

of yanone (empty, plastic 35 mm film canisters make great containers

for the small, loose items). For tools, a small knife, pliers, and a

cigarette lighter (to soften glue and to expand the metal tips) are handy.

Also include several types of glue including a white wood glue like Elmer’s

(R), and Krazy (R) Glue (or equivalent). To build up the nocking area

on a new tsuru, a pair of small wood blocks and a length of hemp twine

along with white wood glue are necessary. One or two small rags are also

handy to have (to wipe the glue from your fingers and the excess glue

from your equipment, for example).

Styles

Archery in Japan has maintained two distinct paths since its genesis.

First, there is ceremonial archery, which has roots in shamanic traditions

and Shinto coupled with direct importation from China during the first

millennium A.D.; Ogasawara Ryu, which includes yabusame, and post-Meiji

Honda Ryu belong to this form of archery. These styles are rarely seen

outside of Japan.

Second, there are the combat and combat-derived archery practices; all

these styles of kyudo are branches of the Heki Ryu. Since World War II,

many of the branches of the Heki Ryu have been united under the aegis

of the Zen Nippon Kyudo Renmei (All Nippon Kyudo Federation, aka ANKF).

Some branches such as the Chikurin-ha have remained independent; other

branches, while belonging to the ANKF, also retain the individual practices

of their ryuha. A few independent schools of Kyudo, such as the Chozen-ji

Kyudo (see Morisawa, 1984, and Kushner, 2000) from Hawaii, have also

arisen.

Ranking

The ANKF style of kyudo is formulated as a gendai (modern) budo, and

rank is based on the kyu-dan (beginner grades and advanced degrees) system.

The ANKF lists testing requirements for san-kyu (grade level three) through

kyu-dan (ninth degree). Challengers for grade perform in front of a test

committee, and are judged according to their performance.

In the older styles, “rank” as such follows the koryu model.

There are at least three levels after achieving a basic proficiency: “assistant

instructor,” [regular] “instructor,” and “senior

instructor.” Unlike menjyo (ranking or grading certificates) given

in gendai budo, kobudo (classical martial ways) issue menkyo (scrolls

with titles) or titles associated with scrolls; in general, these menkyo,

except for the initial one, are teaching licenses, and recognize a level

of competence, proficiency, character and capability for accurate transmission.

The number of menkyo is generally fewer than the number of menjyo with

a minimum of four (the actual number depends on the particular ryuha).

The rank structure of Chozen-ji Kyudo is unknown. Since they are not

affiliated with any ryuha or the ANKF, and since Chozen-ji is dedicated

to making Zen accessible to all, one assumes that kyudo as Zen would

not be ranked. However, they do use the instructor titles of renshi (trainer),

kyoshi (instructor), and hanshi (master instructor), but how these are

conferred is not known.

Training Facilities

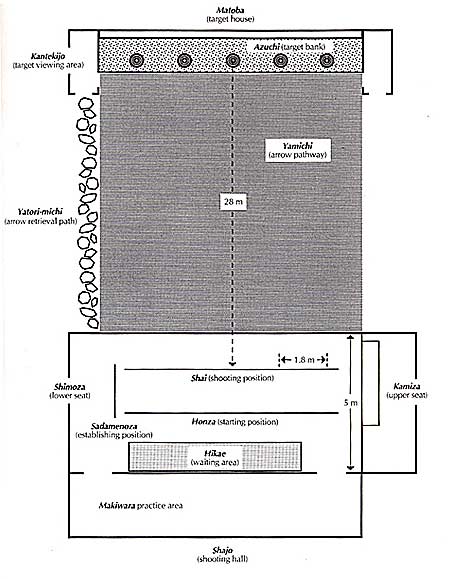

The classical kyudojo is truly a sight to behold; it is composed of

three parts: the shajo (shooting hall), the matoba (target house), and

the yamichi (literally, “arrow way/path”), which is the open

flat ground between the two structures. Within the shajo, there are two

basic areas: the makiwara shooting area, and the distance shooting area

from the side of the shajo that is open to the yamichi and matoba (the

distance shooting area also includes a waiting area). Within the shajo

are also yumi racks, ya boxes and equipment storage. There are a few

kyudojo with a matoba and yamichi, but no shajo; in place of the shajo

is an outdoor shooting platform.

(Courtesy of Kodansha International) (6)

Like the shajo, the matoba is a building with one side open; generally,

the open side of the shajo can be closed or secured in some fashion against

the elements. Within the matoba is the azuchi (target bank), the target

bank of sand, into which the mato are set. The azuchi requires some care

- neatness from raking and firmness from watering. A large and well-designed

matoba has a viewing area where a ya-retriever can safely sit during

a shooting session, and storage for mato and maintenance equipment.

The yamichi can simply be a well-trimmed lawn or a flat area of soil/sand.

Ya that come up short end up in the area of the yamichi in front of the

matoba. A close-cropped lawn will help protect the ya from damage, and

allows for easy retrieval of those ya that do fall short.

|

The Matoba and Azuchi at Seiko

Kyudojo, Karme-Choling, Barnet, VT.

(Courtesy of the author) |

In Japan today, there is generally a municipal kyudojo in the more populous

urban centers. Outside of Japan, these are few and far between. In urban

and suburban areas outside of Japan, limitations on space (as well as

land, construction and maintenance costs) tend to relegate regular practice

to makiwara kyudojo - rooms with high ceilings where one can shoot short

distance at makiwara. It may be a permanent set-up or one that is shared

with other activities, which means that the makiwara must be set up and

then broken down and stored for each practice session. Some individuals

set one up at home for their own practice either indoors or outdoors.

For gatherings at sites with no kyudojo, there are temporary kyudojo.

Makiwara can be set up outside, or under a large tent during inclement

weather. The yamichi can be designated by markers, with a backstop of

hay/straw bales, possibly backed by an arrow net, and the shooting line

designated by a pegged-down rope. Great care must be taken to insure

that other people are kept away from the shooting area, and that the

kyudo-ka are constantly aware of when areas are in use. For many kyudo-ka,

distance shooting is a luxury, and generally occurs only during gasshuku

at some remote site for a period of several days.

History

The history of kyudo remains rather obscure in the West with a very

few sources. Onuma (1993) presented one of the first histories, albeit

somewhat abbreviated. Hurst (1998) has one of the first (if not the first)

comprehensive histories in English, but it is highly biased by his overly

simplified thesis that these activities must evolve from bujutsu (martial

science) to budo (martial way) to martial sport (see Sosnowski, 1999b,

for a critical review).

The long bow is present with the legendary first emperor of Japan, Jimmu,

(c. 660 B.C.). In reality, this is about a millennium too soon for the

historical evidence for the rise of a Japanese state. In the first half-millennium

of this state (4th through the 9th century), the Chinese culture, including

ceremonial archery, was actively imported into Japan, and formed the

basis of Japanese culture. However, the Chinese ceremonial bow is a small,

symmetric recurved bow.

By the Heian period (794-1185), the long bow as a combat weapon, especially

as used by upper-class warriors on horseback, was firmly established – long

before the katana (the so-called “samurai sword,” which is

technically a saber) became the “soul of the samurai,” the

weapon associated with the ruling warrior class was the yumi. During

the Kamakura period (1185-1333), archery equipment experienced several

technological advances in materials, which included lacquered, laminated

bamboo bows, shooting gloves, reliable bowstrings and heavier arrows

to support a variety of iron arrowheads. The long bow remained popular

as both a ceremonial instrument and a battlefield weapon, and this trend

continued into the Muromachi period (1336-1573). During this time, the

Ogasawara, Takeda, and Ise families came to prominence as the premiere

ceremonial archers, and they recorded the practices of their arts in

several treatises.

|

Samurai often wore armor and

carried a bow in addition to their long and short swords. (Courtesy

of Christopher Caile) |

During the Sengoku Jidai (1477-1603), a period of continuous civil war

with various daimyo (war lords) jockeying for position as shogun (chief

war lord), saw the end of kyujutsu due to the introduction of firearms

into warfare by Oda Nobunaga in 1575 in the battle of Nagashino (immortalized

in the 1980 film “Kagemusha” [Shadow Warrior] by the late

Akira Kurosawa, and marked the demise of the Takeda family as a political

power and the loss of their influence in archery), which led directly

to the genesis of kyudo as a way to preserve the practice while developing

character. As such kyudo is an amalgam of kyujutsu and ceremonial archery.

During this time, kyujutsu briefly came into its own due to the genius

of Heki Danjo Masatsugu (1443-1502). When he was almost forty years old,

he realized a new and devastating method of combat archery (prior to

this, there was very little formalized teaching), which eventually became

the Heki Ryu; all combat-based styles can be traced to Heki Ryu Kyujutsu.

All of the daimyo of the latter part of the Sengoku Jidai, including

Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, were schooled in

the Heki Ryu. The effective use of Heki Ryu Kyujutsu lasted less than

a century. A number of styles were derived from Heki Ryu and a number

of branches continued on including the Chikurin-ha, Insai-ha (Hoff, 2002)

and Sekka-ha (Onuma, 1993, and DeProspero & DeProspero, 1996). Much

of this early history is somewhat suspect in part, being derived from

documents whose purpose was to present a long and exalted lineage rather

than being historically accurate.

Heki Danjo was directly succeeded by Yoshida Izuma no kami Shigekata

(1463-1543). The branches of the Heki Ryu are traced to offshoots from

the Yoshida family. Shigekata taught his son and heir Sukezaemon Shigemasa

(?-1569) who, in turn taught his first son and heir, Sukezaemon Shigetaka

(1509-1585), forming the main line of succession for the Izumo-ha, which

is derived from the title of the founder, “Izuma no kami.”

Shigemasa’s fourth son, Shigekatsu (1514-1590), is better known

by his nom-de-plume, Sekka (“snow bearing”). He also studied

Ogasawara Ryu under Ogasawara Hidekiyo. He passed the Sekka-ha on to

his son and heir, Rokuzo Motohisa.

Katsuramaki Gempachiro (1562-1638), later known as Yoshida Issuiken

Insai, married the daughter of Shigetaka’s son and heir, Shigetsuna,

whom he initially studied with. He later studied with Shigetaka’s

third son, Masashige (who also established a branch to be carried on

by his first two sons, and whose third son established another branch),

before establishing his own branch, the Insai-ha. Insai served both the

ill-fated regent Toyotomi Hidetsugu and the first Shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu,

and taught archery to the second and third Tokugawa Shoguns.

Ishido Chikurin (?-1605) was a Shingon Buddhist priest at the Yoshida

family temple. He studied Izuma-ha with Shigemasa as well as the main

line Heki Ryu with Yuge Yarokuro. Having left the priesthood and married,

his son and heir continued the Chikurin-ha in what is now present-day

Nagoya.

|

This old woodblock print depicts

opposing samurai in pitched battle. While most warriors were on

foot, several are also seen on horseback

as opposing swords clash and arrows fly past. Before the introduction

of western firearms, the bow was the premier instrument of choice

for long range firepower.

(Courtesy of Christopher Caile) |

The founding of the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1868) brought profound

changes to the samurai and their practices. The practice of kyujutsu

was the first to change; it became Kyudo, “the way of the bow,” and

it was unique in that it was available to men and women. Modern historians

have placed unnecessary weight on the toshiya competitions at Sanjusangendo,

a hall in the Rengeoin Jingu in Kyoto. The hall is 396 ft (120.7 m) long

but only has a 16 ft (4.9 m) clearance in height; there were endurance

events of twelve and twenty-four hours as well as limited events using

one hundred and one thousand ya. Shooting for toshiya requires different

technique (seated, rapid-fire shooting) and equipment (shorter and more

powerful yumi, stronger ya and four-fingered kake) than used for kyudo,

and only a very small fraction of kyudo-ka, trained for these contests.

Wasa Daihachiro, who trained in the Chikurin-ha, holds the record at

Sanjusangendo, having made 8,133 hits (out of 13,053 or 62.3%) in the

twenty-four hour, full-hall distance shooting event in 1686 (that is

an incredible average rate of one arrow every 6.6 seconds sustained over

a 24-hour period!).

|

|

The grandfather of Kanjuro Shibata, Kanjuro Shibata; the harness

is used for the 24-hour endurance shooting at Sanjusangendo Jingu

in Kyoto [date unknown]. (Courtesy of Zenko International) |

Kanjuro Shibata preparing for the 24-hour endurance shooting at

Sanjusangendo Jingu in Kyoto. (Courtesy of Zenko International) |

During the Meiji period (1868-1912), kyudo, like so many of the other

kobudo that came into being during the Tokugawa era, declined precipitously

as Japan leaped from an nearly isolated feudal state to modern world

power on the global stage, and Western ways were adopted while the old

cultural ways were discarded as antiquated. The Dai Nippon Butoku Kai

(Greater Japan Martial Virtues Association), founded in 1895, resurrected

many budo practices through standardization and by lobbying the newly

formed Ministry of Education. Arts like judo, kendo, naginata-do (“the

way of reaping sword”), and kyudo became part of the physical education

programs in the Japanese schools; later karate-do was added. In the 1930’s,

many budo practices, with kyudo being an exception, became part of the

quasi-military training given to youth of the Imperial Japanese Empire,

which continued throughout World War II.

A formal portrait of the grandfather and predecessor of Kanjuro

Shibata, Kanjuro Shibata, the former head of the Heki Ryu Bisshu

Chikurin-ha [date unknown] (Courtesy of Zenko International) A formal portrait of the grandfather and predecessor of Kanjuro

Shibata, Kanjuro Shibata, the former head of the Heki Ryu Bisshu

Chikurin-ha [date unknown] (Courtesy of Zenko International)

During the occupation (1945-1952) that followed Japan’s

defeat in World War II, General Douglas MacArthur banned the practice

of all budo, which was viewed as a tool of the vanquished Japanese

militarists. Kyudo was one of the first to emerge from that ban

in 1949. Under American influence, many Budo, such as kendo, judo

and karate, emerged with a strong sports-like component; this also

included kyudo. The ANKF emerged as the governing body for standardized

kyudo; however, several ryuha, including the Chikurin-ha, remained

independent of this unification effort. Ceremonial styles such

as the Ogasawara Ryu, and synthetic styles like the Honda Ryu (a

Chikurin-ha and Ogasawara Ryu amalgam developed at the end of the

19th century as part of Honda Toshizane’s effort to keep

kyudo viable during its decline in the Meiji era) continued on

as well. |

Kyudo: The Essence and Practice of Japanese Archery is available

from the FightingArts Estore:

(160 p., 7½ x 10½"

hardbound., fully illustrated)

US$32.95

(+$5 shipping within US)

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank my three reviewers, Dr. Deborah Klens-Bigman of New

York City, Dr. Dennis Martin of Winterport, ME, and an anonymous ANKF

instructor, for their efforts in tackling the first draft of this work,

and for making many helpful suggestions for improvement. I would also

like to thank Kodansha International for granting permission to reproduce

illustrations from their book “Kyudo –The Essence and Practice

of Japanese Archery,” by Hideharu Onuma with Dan and Jackie DeProspero,

as well as Dan and Jackie DeProspero themselves who have also allowed

use of illustrations from their website to be used in this article series.

An additional thank you goes Christopher Caile who supplied several historical

wood block images.

About The Author:

Raymond Sosnowski began his martial arts training in 1973

at the Stevens [Tech] Karate Club in "Korean Karate," which

was then a euphemism for Tae Kwon Do; he trained for over sixteen years

in the ITF (International Taekwondo Federation) style, teaching for the

majority of that time. He has practiced Kuang P'ing Yang style T'ai-Chi

Ch'uan for twelve years beginning in 1987, and taught for several years,

giving several local seminars. His first weapons were the T'ai-Chi [straight]

sword and the Chinese iron fan. He came to the Japanese martial arts

in 1991, initially training in Aikido, first Shodokan (Tomiki-Ryu) and

then Aikikai style, and Aikido weapons (aiki-ken and aiki-jo). Training

in Japanese weapons began in 1996 with Iaido, Jodo, Kendo and Naginata;

Kyudo was added in 1997. He is a yudansha (or equivalent) in all these

arts, as well as an assistant instructor of Kyudo, and an instructor

of Iaido and Naginata. The study of Nakamura Ryu (along with Toyama Ryu)

Batto-do was added in 2003. He is also a student of Zen and the Shakuhachi

("Zen flute"). Sosnowski was a co-founder (1998) and the first

Secretary of the East Coast Naginata Federation as well as the principal

author of their by-laws. He was a co-director of the Guelph [Ontario]

School of Japanese Sword Arts (GSJSA) in 1998, 1999 and 2000, and made

presentations at the panel discussions during the GSJSA in 1999 and 2000.

In addition, he was a contributing author of articles, book reviews and

seminar reports to the now-defunct publications "The Iaido Newsletter" (TIN),

and "Journal of Japanese Sword Arts" (JJSA), in addition to "Ryubi

-- The Dragon's Tail (the newsletter of Kashima Shinryu/North America)." Current

and revised writings appear in "The Iaido Journal" section

of EJMAS (Electronic Journals of Martial Arts and Sciences) at <http://ejmas.com>.

He is an occasional contributor to Iaido-L, e-Budo, the Kendo World forums

and Sword Forum International. In his professional career, Mr. Sosnowski

is an Engineering Fellow and Technical Director of Maryland Technical

Center for Sonetech Corporation (with headquarters in Bedford, NH), specializing

in artificial intelligence methodologies and computer-based numerical

analyses, as well as being an expert in all phases of software development

including government documentation. He holds three masters degrees, [Physical]

Oceanography from the University of Connecticut (Storrs, CT), [Applied]

Mathematics from Rivier College (Nashua, NH), and Cognitive and Neural

Systems from Boston University, as well as a Bachelors in Physics from

the Stevens Institute of Technology (Hoboken, NJ). He lives with his

wife Valerie in rural Maryland between Washington, DC, and Baltimore,

MD, described by a friend as "a little piece of southern New Hampshire

in Maryland."

|