The Samurai, The Ship And The Golden Gate

By Romulus Hillsborough

In January 1860, the Tokugawa Shogunate, the feudal military

government which ruled Japan for over two and a half centuries, dispatched

an official delegation to Washington to ratify the first commercial treaty

between Japan and the United States.

| |

Japanese mission members including Katsu Kaishu,

Fukuzawa Yukishi and Jehn Manjior. The San Francisco “Evening

Bulletin described the arriving Samurai (officers) on March 19,

1860, as “wearing polished samurai swords, two each. Every

man’s hair was got up without regard to expense, lavishly

greased…and carefully dressed. Their dress bears some resemblance

to that of the richer Chinese, but exhibits a taste of more harmony

with our own.” There were… “innumerable servants,

who with bowed head, received orders and answered questions for

their superiors.” |

The members of the delegation sailed aboard a U.S. Navy steam frigate.

In advance of the delegation, the shogunate sent the tiny schooner Kanrin

Maru. In command of the Kanrin Maru was a fascinating man by the name

of Katsu Kaishu – an expert swordsman who refused to draw his sword,

founder of the Japanese Navy, and one of the most revered personages in

Japanese history. Accompanying Captain Katsu and Company was U.S. Navy

Lieutenant John M. Brooke, who criticized the Japanese for their lack

of maritime expertise.

U.S.

Navy Lieutenant John M. Brooke, who criticized the Japanese for

their lack of maritime expertise. Interestingly, in April 1861 with

the succession crisis deepening, Brooke resigned his commission

and joined the Confederate Navy. Soon afterwards he was deeply involved

in the conversion of the burned steam frigate Merrimack into the

ironclad CSS Virginia and in the design and production of heavy

rifled guns for the Southern war effort. U.S.

Navy Lieutenant John M. Brooke, who criticized the Japanese for

their lack of maritime expertise. Interestingly, in April 1861 with

the succession crisis deepening, Brooke resigned his commission

and joined the Confederate Navy. Soon afterwards he was deeply involved

in the conversion of the burned steam frigate Merrimack into the

ironclad CSS Virginia and in the design and production of heavy

rifled guns for the Southern war effort.

|

Their inexperience in practical navigation notwithstanding, each of the

samurai of the Kanrin Maru was endowed with a special sense of duty and

integrity which was distinctly Japanese. This special sense of duty and

integrity was known as “giri.” It was a duty based on favor

received, and an integrity founded on a sense of shame. Giri accounted,

to a great extent, for the harmony in samurai society, and it was an inherent

element of both the beauty and the moral strength of the samurai class.

Giri would serve as a foundation for the formidable power of the future

Japanese Imperial Navy, and Captain Katsu had incorporated it into the

regulations of his ship's company, and indeed those of the shogun’s

nascent navy. Kaishu admonished his officers "not to employ the service

of the sailors for other than official purposes," and, in this regard,

wrote: "In other countries the navy or the army, as the case may

be, decides how it will use its officers and rank and file – and,

in fact, uses them as if they were slaves. Based on severe regulations,

if a subordinate does not obey the orders of a superior officer, he will

be dishonorably discharged by order of the top commander. But Japan is

unlike other countries. We command the hearts and minds of our people

through [their sense of] duty [based on favor received], and integrity

[founded on their sense of shame]. However, unless superiors treat their

subordinates with a warm heart on an everyday basis, the subordinates

will not act in harmony with their superiors in the face of a life-threatening

situation. And unless a superior works and worries ten times as much as

his subordinates, he will not be qualified to lead others." Katsu

Kaishu’s words of wisdom would best be heeded by leaders in today’s

troubled world!

|

|

| Navy Commodore Matthew Perry |

Perry and his delegation presenting a letter

from the US President to the Japanese authorities |

|

One of Perry's ships (Japanese

woodblock print) |

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the Kanagawa Treaty. Signed

on March 31, 1854, it is also known as the Treaty of Peace and Amity –

certainly a misnomer! The treaty, in fact, was a result of the gunboat

diplomacy of U.S. Navy Commodore Matthew Perry, whose flotilla of four

warships had threatened Edo (modern-day Tokyo), the shogun’s capital,

in the previous summer. The Kanagawa Treaty officially inaugurated diplomatic

relations between the United States and Japan, and marked the beginning

of the end of Tokugawa rule. Under the Tokugawa Shogunate, Japan had been

isolated from the rest of the world. As part of its isolationist policy,

the shogunate had banned the building of large oceangoing vessels to prevent

would-be insurgents from venturing overseas. As a result, Japan did not

have a navy. After the arrival of Perry, the small island nation was compelled

to develop a modern navy to preserve its sovereignty. Katsu Kaishu realized

this, just as he knew that modern technology would be essential to this

end. But Katsu was a nobody, the son of a petty samurai without an official

post. Fortunately for the future of Japan, however, he was also a shining

light of progressive thought – in a land ruled by a technologically

and politically backward regime. Katsu had submitted a letter to the shogun’s

government, in which he pointed out that Perry had been able to enter

Japanese waters unimpeded only because Japan did not have a navy to defend

itself. The shogunate must establish a navy, he professed. He advised

the shogunate to lift its ban on the construction of warships needed for

national defense; to manufacture Western-style cannon and rifles; to reform

the military according to modern Western standards; to establish military

academies. He was subsequently recruited into government service, and

received training at the new Naval Academy in Nagasaki.

Katsu

Kaishu. He was a samurai, and founder of the Japanese Navy whose

protégé was Sakamoto Ryoma, a central player in the

overthrow of the Tokugawa Shogunate. Kaishu was a street-wise

statesman and outsider with interests in technology and modernization.

He was also an historian and prolific writer. In addition to Ryoma

he mentored many who became heroes of the Meiji Restoration (advent

of modern Japan). Katsu

Kaishu. He was a samurai, and founder of the Japanese Navy whose

protégé was Sakamoto Ryoma, a central player in the

overthrow of the Tokugawa Shogunate. Kaishu was a street-wise

statesman and outsider with interests in technology and modernization.

He was also an historian and prolific writer. In addition to Ryoma

he mentored many who became heroes of the Meiji Restoration (advent

of modern Japan).

|

One cold morning in early 1860 Captain Katsu was down with a fever.

He sat alone in his study at his home in Edo, his mind occupied with more

pressing matters than his immediate physical condition. “Rather

than die like a dog at home,” he would recall decades later, “I

thought that it would be better to die aboard a warship. The day had arrived

when we were to set sail, and not concerning myself with the throbbing

pain in my head, I told my wife that I would go… and have a look

at the ship,” so that his wife expected him to return soon. He would

not be back for four months.

|

The Karin Maru. When Commodore

Perry with four black ships arrived off Uraga in this city in 1853,

the Tokugawa Shogunate (government of the shogun) realized the importance

of building up its own naval force after more than two centuries

of isolation. It soon requested the Dutch government to build the

warship Japan (250 tons), renamed Kanrin Maru (49 meters

in length, and heavily armed with 16 guns, cannons and a mortar

and howitzer. The cost was $70,000. Many of the Japanese associated

with this ship became public figures in Japan's modernization, including

Katsu Kaishu, Fukuzawa Yukichi, and Enomoto Takeaki. After the Japan-U.S.

Commerce and Trade Agreement was signed in 1858, the Kanrin

Maru, under the command of Kimura Settsunokami, sailed to San

Francisco as an escort vessel to the Japanese mission in the US.

The mission’s purpose was to exchange documents of the ratification

of the treaty in 1860. The Kanrin was the first Japanese

vessel to visit the US or any foreign country for centuries. |

|

A Japanese woodblock print

depicting the stormy voyage of the Kanrin Maru in 1860. |

Not long after departing, the Kanrin Maru

ran into one of the worst typhoons ever encountered in the Pacific.

An American Officer, U.S. Navy Lieutenant John M. Brooke, and nine

other American sailors under his command, helped save the ship.

The Kanrin plodded ahead, and after 37 days at sea, she

finally dropped anchor in San Francisco harbor. The Japanese mission,

sailing aboard the US naval warship Powhatan, did not arrive

until twelve days later. On arriving in San Francisco Bay the Japanese

Admiral in charge of the ship made a handsome present in money to

each American. On board were also US Army officer Capt. Burke, a

civilian E.M. Keen. For a more detailed story on the passage of

the Kanrin Maru click

here.

|

|

|

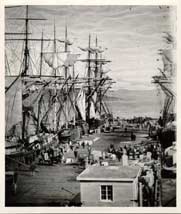

| How San Francisco Bay must have

looked to the visitors as they arrived in 1860. |

A view of a busy San Francisco wharf at Vallejo

Street in the early 1860's. The port was a major trading and immigration

center. |

|

Another image of San Francisco

in 1860 looking across the city toward the bay. |

On the morning of March 17, on her thirty-seventh day of passage, the

Kanrin Maru sailed through the Golden Gate of San Francisco, and became

the first Japanese vessel to reach the Western world. At her mainmast

and bows flew white banners emblazoned with the red Rising Sun. The local

San Francisco press made much ado about the arrival of the Japanese ship,

while Captain Katsu and his samurai crew reeled from culture shock. In

1860 San Francisco, with a population of 56,000, was the economic and

cultural center of the western United States. When the two-sworded, top-knotted

gentlemen from Japan dropped anchor off Vallejo Street Wharf shortly before

sundown, amidst an eclectic gathering of merchant ships flying flags of

every nation, their eyes were treated to a cosmopolitan feast which could

only have exceeded their wildest expectations. According to a local newspaper,

“the crew cast long and wistful eyes ashore at the city, whose strange

sights they were doubtless eager to explore.” Captain Katsu made

a grand impression on the San Franciscans, who discerned in him a likeness

to former explorer, Gold Rush millionaire, California senator, and recent

Democratic presidential candidate John Charles Fremont: “The Captain

of the corvette is a fine looking man, marvelously resembling in stature,

form and features Colonel Fremont, only that his eye is darker, and his

mouth less distinctly shows the pluck of its owner.”

|

|

How San Francisco looked in 1860.

It was an amazing sight to the Japanese visitors. San Francisco

at the time was a thriving commercial town with exploding growth

following the California Gold Rush of 1849 and the 1850’s.

By ship and by wagon train a flood of treasure seekers from the

US and immigrants from Latin America, Europe, Australia and Asia

had swollen San Francisco. |

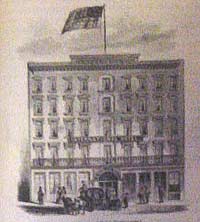

The International Hotel on Jackson

Street. Built in the mid-1850s, it was one of several new first

class hotels to spring up in San Francisco at this time when the

city was undergoing explosive growth. Located in the center part

of the city, the five-story hotel boasted elegant furnishings and

250 furnished rooms. Visitors could pay on a daily or weekly plan.

Boarders were provided meals from a restaurant on the premises.

The Japanese Samurai visitors probably housed there because the

hotel was convenient to the steam and sailing ship landings. |

Upon disembarking, the samurai entourage proceeded by carriage to the

International Hotel on Jackson Street. That Captain Katsu, unlike most

of his countrymen, had previously familiarized himself with Western customs,

dress and furnishings, and even cigars and champagne (although, as a rule,

he did not drink alcohol), is indicative of the elasticity of his very

open mind. That he did not blindly prescribe to standards of samurai dress,

but rather wore his thick black hair tied in a loose topknot, so that,

according to the local press, “he looked as if he knew nothing of

pomatum and gloried in its frizzled, shaggy look,” speaks loudly

of his outsider’s nature. That he did not seem to depend on an interpreter

because, while the others “did not understand all that was said

to them,” their captain was “acquainted with the language,”

speaks for his command of self-possession, because, in truth, Katsu did

not understand English either.

Captain Katsu had come to the United States resolved to introduce democratic

ideas and American technology into Japan. He did not, however, proclaim

this resolve to his less informed, and less enlightened, colleagues –

most of whom had inherited their privileged positions from their fathers,

and with whom he was constantly at odds, even as they sat in the exquisite

parlor of the International Hotel, exchanging niceties with Americans

whose government’s gunboat diplomacy had rent Japan asunder. Rather

he would save his resolve for great and kindred souls, namely Sakamoto

Ryoma and Saigo Takamori, who in less than eight years’ time would

overthrow the regime in whose service Katsu repeatedly risked his life.

Katsu’s resolve was bolstered by his farsightedness. He was a visionary

who was beginning even now to see the inevitability of his government’s

collapse – which was why, in just four years, when his house arrest

was imminent for harboring known revolutionaries, most notably Ryoma,

he would, as commissioner of the Tokugawa Navy, meet with Saigo, one of

the Tokugawa’s most formidable enemies. He would realize then that

the future of Japan no longer rested with the shogunate, but with a unified

and representative Japanese government. He would press upon Saigo the

absolute necessity for the warring samurai factions to unite if Japan

was to have a future at all. This, of course, was eventually what did

happen, with the overthrow of the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1868.

The samurai entourage savored their sojourn in the burgeoning silver

metropolis beside the Golden Gate. They walked the Victorian streets.

They entered a photographic studio on Montgomery Street. They toured the

waterfront near the Vallejo Street Wharf, viewing with keen interest a

merchant ship from Panama. Captain Katsu visited the San Francisco Baths

on Washington Street, because he “was desirous of trying the American

style” of bathing. He road the sand cars on the Market Street Railway,

and observed local factories. (Years later Katsu expressed his disbelief

at the spectacle of a factory worker openly engaged with a prostitute

during break time, and his perplexity at being offered “the wife

of Mr. So-and-So for a certain amount per hour.”) Captain Katsu

explored the shops in town, his interest particularly aroused by Keith’s

Apothecary, because on the previous day one of his sailors had died of

illness. He went to the marble yard on Pine Street to order a gravestone,

on which he wrote an epitaph for the burial which took place in the grounds

of the Marine Hospital. The samurai noted his repulsion at the sight of

large pieces of beef and pork at the front of a butcher shop, “covering

my nose as I passed by.”

One evening Captain Katsu was invited to a dance party at the San Francisco

home of a United States Navy officer. The samurai was impressed by the

“courtesy of everyone,” and wondered at the strange customs

of the Americans. “The men put their arms around their wives’

shoulders and waists to dance… [One man] took the hand of another

man’s wife to dance.” From the eyes of a man born and bred

amidst the mores of feudal Japan, even one as well-versed in things Western

as Katsu Kaishu, the dance party was certainly a strange spectacle. A

man of the samurai class simply did not bring his wife to a social gathering.

It would have been a gross violation of protocol. He would no sooner do

so than he would leave home without his swords, forsake liege lord or

clan, or relinquish his warrior status. The notion, in fact, never crossed

his mind. Whether or not Captain Katsu danced with the wives of his American

hosts, he particularly enjoyed the ice cream they offered. “And

the champagne, served with crushed ice, was most delicious. People in

Japan have never tasted anything like it.” After a stay of nearly

two months in San Francisco, the Kanrin Maru set sail on May 8, returning

safely to Japan soon after.

On a bluff in overlooking the Golden Gate in lush Lincoln Park in the

northwestern extremity of San Francisco, stands a stone monument to the

Kanrin Maru. Dedicated in 1960, it was a gift from the city of Osaka to

commemorate the 100th year since of the Japanese ship’s historic

voyage. As mentioned above, this year marks the 150th anniversary of the

Kanagawa Treaty. Both this monument and this anniversary must also celebrate

the life and times of the ship’s captain, who rose to become one

of the greatest men in Japanese history.

Acknowledgements:

Permission to use the photo of Katsu Kaishu by FightingArts.com was

provided by Takaaki Ishiguro, a photo collector currently living Tokyo.

Harbor views of San Francisco provided courtesy of www.BoatingSF.com.

The S.F. street scene was a cropped enlargement of this image.

Photo of the Japanese mission members was declared as to be in the

public record by the Japanese government.

The image of Perry and his delegation presenting a letter from the

US President to the Japanese authorities provided complements of Kauai

Fine Arts located in Lawai, Hawaii.

S.F. Warf photo from 1860 provided with permission of the S.F. Historical

Center, S. F. Public Library.

Drawing of the International Hotel in San Francisco from the book “Annals

of San Francisco” by Frank Soule, John H. Gibon M.D. and James

Misbet published by D. Appeton & Co. 1885, Copyright 1884, p. 650.

About The Author:

Romulus Hillsborough is an acclaimed writer and teacher of Japanese History.

His books include RYOMA - Life of a Renaissance Samurai (Ridgeback Press,

1999), Samurai Sketches: From the Bloody Final Years of the Shogun (Ridgeback

Press, 2001), and Shinsengumi: The Shogun’s Last Samurai Corps (Tuttle

2005). Hillsborough has been a regular contributor to FightingArts.com. |