"Yoi" & The First Preparatory Moves Of Kata

By Christopher Caile

Recently at the end of a particularly hard class workout, a visiting

student from England approached me and asked about the meaning of the

first preparatory move in kata.  The

move is signaled by the 'yoi' (the command often used in Japanese karate

to signal getting ready to do a kata) and can be quite subtle or large

depending on the style and system.

The

move is signaled by the 'yoi' (the command often used in Japanese karate

to signal getting ready to do a kata) and can be quite subtle or large

depending on the style and system.

I had heard the same question many times before. It is a difficult

question since kata don't come with instructions, and there are different

interpretations, especially between the Chinese systems, Okinawan and

even Japanese kata, styles and systems. Also kata are what you make

of them, and an awareness of what you are practicing is important.

There is also some evidence that in Okinawa, the birthplace of karate,

that kata before the modern era often did not begin with a preparatory

"yoi" move or with the same standard ready posture. Teachers

such as Chojun Miyagai (founder of Goju Ryu) are said to have standardized

kata beginnings with these additions. Thus, at the very least these

movements identify, mark or symbolize the system or style within which

the kata are practiced. But I think there is much more.

In Goju ryu and some other styles of karate, the hands meet in the

middle, one hand over the other. The heels of the feet are together

with the toes pointing outward (musubi dachi). In Goju Ryu kata there

is more emphasis on the mental aspect of preparation. A command "mokuso"

is used to signal students to close their eyes and calm their mind without

thoughts before the "yoi" is voiced. In other styles, an open

palm of one hand covers the fist of the other. In Shotokan and in some

katas of Seido, Kyokushin, Oyama karate and others the arms are often

held apart, down and in front and (parallel) outside of the legs which

are in a natural stance, the toes slightly flared (fudo dachi). It is

here that the mind is focused and controlled (although there is no "mokuso"

command, as voiced in Goju Ryu, expressly voiced for that purpose).

When the command "yoi" is heard (or, when the kata is done

alone, when a silent beginning is internally voiced) the arms move in

some characteristic action -- as small as a drawback to the sides of

the legs or as large as bringing the arms up, both hands starting at

opposite ears, followed with a lowering of them to the sides.

Although more pronounced in some systems, the preparatory movement

includes a forced out breath (ibuki breathing), the hips tucked forward

under the body trunk along with body tensing followed by relaxation

(still slightly tensed ready to go into action) as well as foot/leg

rotation outward under tension (having first been turned in). All this

may be subtle or very overt, but nevertheless evident in most karate.

In the few Chinese styles I have studied the initial move seems much

more perfunctory, and is given less emphasis than in karate, especially

Japanese karate.

So what is happening? First we should realize that kata is a lot more

than just technique. Kata are performed on other levels too, including

the strategic, psychological, spiritual and physical (body). Here, I

think, what we are seeing is these other levels, and a lot is going

on at once -- things most people never pay attention to.

Imagine this scenario. You are walking alone down a street, path or

sidewalk. It's night and it's deserted. Suddenly you are aware of several

men approaching. They are young, with black jackets and one has a headband.

They look drunk. Your mental alarm goes off and you feel the hair on

the back of your neck stand up. You ask yourself, should I run, or is

it really something innocent? Maybe I am mistaken. But then they are

around you, pushing your chest, one man demanding that you hand over

your wallet. You feel sick, cold sweat on your forehead. Fear is now

tangible. The mind shouts, 'do something,' but you feel frozen, as your

heart pounds, your breath racing. Even your vision seems to narrow,

as if looking down some tunnel. This is not the dojo, this is not some

self-defense practice -- you know your life is in danger. This is real,

and fear and anxiety take control -- paralyzing your mind and forcing

physiological reactions that limit your ability to respond.

In some karate styles or schools, during class practice of kata, students

begin with a 'rei," or bow to the teacher. This precedes the "yoi"

called out by the instructor to signal to each student to get ready

to engage in the kata's particular portrayal of a combat situation.

The actual kata begins with the order to start (hajime), or with a count

signaling students to perform the first move of a kata. While the yoi

is not vocalized when kata is practiced alone or demonstrated outside

a group class, the preparation is very much as real -- you are getting

ready to perform kata, kata which is combat codified within sequences

of movement. So, "yoi" can be best understood as the signal

to begin self-preparation for combat -- preparation to face not only

opponents but also the self -- the mental and psychological barriers

noted above. And there is an element of strategy too. At the end of

the preparatory movement, you are softly tense, like a calm tiger ready

to move explosively if necessary, but still not taking the offensive.

This is the THE REAL BEGINNING OF KATA.

Let's look at what happens in the first preparatory move. You take

a deep in breath and forcefully exhale (ibuki breathing). This can be

pronounced or subtle. This takes care of the natural body reaction to

intense stress -- hyperventilation. Your arms (and it doesn't matter

the exact movement patterns) move to tighten and then slightly relax.

So do your legs and torso. You have taken control of your body. Your

eyes and mind focus on everything and nothing, repeating in microcosm

the years of quiet meditation that allowed you to abstract the self

from all emotions and thoughts -- but this time to relax the mind and

maximize total awareness (zanshin), settling the self in the lower abdomen

that is pressed forward (proper posture) to align the body and its energy

pathways -- a center also recognized for its sixth sense or intuition.

You are ready to move into action instantly or continue to be alert

and ready after action. Others will recognize this position as the same

one necessary to align the hips with the spine so as to provide efficient

power (see the article, "A Simple Lesson in Body Mechanics").

There is an old samurai saying, "When the battle is over, tighten

your chin strap" (of your helmet). Police officers have observed,

for example, that immediately following an arrest, when an officer feels

that danger is over, is actually the most dangerous time: the inclination

to relax occurs at the same time the prisoner may be desperately searching

for an opportunity to escape.

This mental state can have profound effects. Have you ever been in

an auto accident, and in the last second or fraction of a second seem

to experience the world in slow motion as the accident played out across

your mind? This is a Zen moment of total awareness, but unfortunately

one imposed upon your mind by the intensity of the situation. Think,

if you could control this feeling and see a confrontation unfold slowly

while maintaining a mental state within which you could freely act without

psychological reactions clawing against your every move. That is what

Zen type meditation can give you. It is also something which can be

practiced through kata. Kata can be viewed as planning for and execution

of practiced reactions to stressful contingencies.

The effectiveness of this preparation, however, can vary tremendously.

If we just perform the "yoi" preparatory move, even thousands

of times, in a normal mental state, little will be achieved. But if

you self-prime your mental engine with fear, your "yoi" move,

both physical and psychological, will have an actual state of high anxiety

to play off against. How is this done? You might dredge up moments of

intense fear experienced in the past, or try to create a vivid image

to do the same. Then after much practice your preparatory move creates

a psychological reaction -- the preparatory move being associated with

control of mind, body and breath in the face of anxiety or fear. You

create a conditioned response. Anytime anxiety strikes you can easily

counter it, even at home or at the office -- your preparatory move in

kata, even if performed in a very subtle manner, will still elicit those

responses that the body had been programmed to follow.

Accompanying this total awareness is spirit -- spirit that fills your

every movement and position, that emanates from your eyes and stance.

My teacher Kaicho Tadashi Nakamura often demonstrates the importance

of spirit in kata. He notes that when you begin a kata you should evidence

a powerful assertiveness, a confident, controlled movement and focused

eyes that emit a powerful spirit and will embedded within your movement

and stance (kamae). These same attributes were reflected by the feared

and legendary Japanese swordsman Miayamato Musahi who said: "When

I stand with my sword against a foe, I become utterly unconscious of

the enemy before me or even of myself, in truth filled with the spirit

of subjugating even earth and heaven."

There are many stories from old Japan that tell of one Samurai recognizing

the mastery of another just by the other's stance, the way he sits or

rides a horse. Thus, just the way you stand at the beginning of the

kata can reflect your assurance, spirit and quality of your technical

mastery.

Many years ago Richard Kim (a much respected karate historian, author

and teacher) made this point to me. During one discussion, Richard held

his two hands apart, pointing the index fingers of each hand. He said

that rarely in karate do we ever experience the reality of life and

death combat, something the Samurai of Japan once faced. "The one

place their spirit can reach out to touch ours," he said as he

touched the finger tips of his hands together, "is within kata."

He noted that within kata we can experience and live the same danger,

the same fear and threat of death that Samurai learned to deal with.

And that should be the highest goal in kata too -- to reach out and

touch the true Samurai spirit from across the centuries.

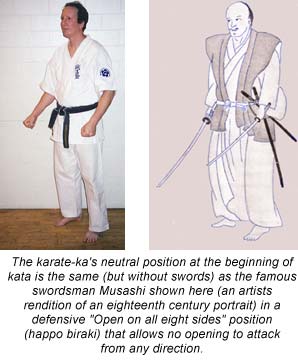

Following the initial preparatory move the feet are parallel or slightly

flared outward (depending on kata and style) and the hands are at the

sides -- a natural stance. This neutral position, without commitment,

contains both defense and strategy. It represents the common position

many people find themselves in when suddenly attacked. To the defender's

advantage is the stance (parallel or fudo dachi), which allows quick

movement in all directions. To his disadvantage are the arms --down

at his sides. The actual first move of kata beyond the preparatory movement,

many argue, starts with a natural startle reflex movement of raising

the arms for protection. Some argue that these movements can be interpreted

as the beginning of various blocks or arm movements which, when completed,

are seen as the first actual moves in the kata, such as the down or

inside one arm block or two arm blocks.

But if an attack isn't in progress or immediate the neutral stance

also contains, etiquette, strategy as well as a psychological element.

Gogen (The Cat) Yamaguchi (Japanese Goju Ryu) in his book, "Goju

ryu Karate-do Kyohan," suggests that while the crossed hands in

front protect the groin from sudden attack, that: at the same time "you

show the opponent that you will not attack suddenly. This was the etiquette

of the samurai. The samurai would take off a Katana (long sword) from

their waist and change it to the right hand showing that their would

not be a cowardly act such as slashing the opponent without notice."

The neutral stance is also defensive since potential threat has not

been reacted to by taking a fighting stance. There is an old Okinawan

saying, "we need two hands to clap" (it takes two to quarrel).

At this point any outward physical attack will automatically trigger

the physical confrontation before the psychological cards have been

fully played. But if an attack has not begun, there remains a physiological

card which might avoid conflict altogether.

Appearing not to react, rather than assuming a defensive stance or

showing fear or intimidation, can be very disconcerting to a potential

aggressor. Remember, aggressors are fearful too. They depend on your

fear and your intimidation. So, a lone aggressor, or several, try to

intimidate you to see how you react. If you don't react on the surface,

this is unnerving. Intimidation and outright fear was expected, at least

some nervous expression, some act of mental reaction that would signify

defeat, or at least some vain and weak attempt at defense. Instead you

are standing there unafraid, almost detached but exuding a confidence

and spirit. "Something is wrong," the attacker (or attackers)

says to himself. "He's not reacting. He is not afraid. What does

he know?" If you are able to do this before an attacker has physically

started an assault, you have put him or them on the mental defensive.

This can be very powerful.

There is an old Japanese story of the Tea Master and the Ruffian that

makes this point. The Lord of Toas Province in Japan, Lord Yamanouchi,

was going to Edo (now Tokyo) on an official trip and insisted that his

tea master accompany him. The tea master was reluctant. He was not a

sophisticated city person and not a samurai. He was afraid of Edo and

the dangers he might face, but he was unable to refuse his master's

request. His master, however,in a conscious attempt to boaster the tea

master's confidence, attired him in Samurai clothing with the customary

two swords. The Lord thought that among the other samurai on the trip,

the tea master would become invisible.

One day after arriving in Edo the tea master decided to take a walk.

The very danger he feared most then confronted him. A ronin, a masterless

samurai, approached him, insisting that it would be an honor to try

out his skills in swordsmanship against a samurai of the Tosa province.

In reality all the ronin really wanted was the tea master's money which

he could get if he killed him.

The shock of this confrontation at first immobilized the tea master.

He couldn't even speak. Finally gaining a little composure, the tea

master explained that he was not really a samurai, and didn't want a

confrontation -- that he was only a master of tea dressed this way by

his master. But the ronin pressed harder. He demanded a test of skills.

He said it would be an insult to the province of Tosa if its honor wasn't

defended.

The tea master didn't know what to do. After thinking it over for a

while he saw no way out of the situation. He became resigned to dying.

But then he remembered he had earlier passed a school of swordsmanship.

The tea master said to the ronin, "If you insist, we will test

our skills, but first I must finish an errand for my master and will

return later when the errand is completed." The ronin, now pumped

up with confidence, readily agreed.

The tea master made his way back to the school of swordsmanship. Luckily,

the master was in and would see him. The tea master explained his situation

and asked the sword master how he might behave correctly, to die like

a samurai, so as to behold his province's honor. The swordmaster was

surprised. He answered that most come to learn how to hold and use a

sword,whereas he had come instead to learn how to die. "Serve me

a cup of tea," said the sword teacher, "while I will think

the situation over."

The tea master cleared his mind. He knew this might be the last cup

of tea he might ever serve. He began his preparation, a practice ritual

performed as if nothing else existed, each movement being a total concentration

on the moment, on the action. Impressed with this performance, the sword

master said, "that's it."

"Tomorrow," said the swordmaster, "when you face the

ronin, use this same state of mind. Think of serving tea to a guest.

Apologize for the delay. And when you take off your outer garment, fold

it and place your fan upon it with the same calm assurances and grace

that you use in preparation of tea. Continue this focus as you rise

and put on your head band. Draw your sword slowly, raise it above your

head and hold it there, like this," he said, "and close your

eyes. When you hear a yell, strike down. It will probably end in mutual

slaying."

After thanking the sword teacher the tea master returned to meet the

ronin, resigned to his fate. Following his advice, the tea master apologized

for the delay and began to prepare himself ceremoniously -- carefully

taking off his outer garment, folding it, and then placing his fan on

top.

The ronin was startled. This fearful figure, who once said he was but

a lowly tea master, had changed. Now before him was total concentration,

poise and confidence -- someone fearless and controlled. The tea master

finally faced his foe and raised his sword as he had been shown. He

closed eyes awaiting the shout that would seal his fate. But nothing

happened. Seconds later when he finally opened his eyes, there was no

ronin to be seen, only a small figure is the distance quickly receding

away.

About the Author:

Christopher Caile, the founder and Editor-in-Chief of FightingArts.com,

is a historian, writer and researcher on the martial arts and Japanese

culture. A martial artist for over 40 years he holds a 6th degree black

belt in karate and is experienced in judo, aikido, daito-ryu, itto-ryu,

boxing, and several Chinese arts. He is also a teacher of qi gong.