20th-Century Arnis

The Reemergence of a Warrior's Art

(Part 3)

By Mark V. Wiley

As human nature usually has it even the best of intentions go awry. During

the course of the revival of Filipino martial arts many of the schools

became rivals and their members would fight against one another to see

who was superior. However, in the hope of once again promoting solidarity

amongst fellow practitioners and schools in Cebu, the Cebu Escrima Association

was formed in 1976. The newly formed Association lost no time in perpetuating

the arts and that same year, in association with NARAPHIL, it sponsored

the First National Arnis Convention and First Asian Martial Arts Festival.

Then, in 1977, in Talisay, Cebu, Grandmaster Florencio Lasola founded

the Oolibama Arnis Club.

Perhaps the most successful association in the central and southern Philippines

in the 1970s was the Tres Personas Arnis de Mano Association. Tres Personas

was founded by Timoteo E. Maranga with

four specific goals in mind: to promote brotherhood and understanding

among the advocates of Filipino martial arts; to encourage and propagate

Filipino martial arts among the youth; to defend the weak, the young and

the old; and to defend the oppressed people, country, and God. Maranga's

martial arts background is varied and includes studies in combat arnis,

judo, karate, and Western wrestling. Tres Personas arnis is a mixture

of the de marina, de cadena, literada, Batangueña serada, florete,

and sumbrada styles. with

four specific goals in mind: to promote brotherhood and understanding

among the advocates of Filipino martial arts; to encourage and propagate

Filipino martial arts among the youth; to defend the weak, the young and

the old; and to defend the oppressed people, country, and God. Maranga's

martial arts background is varied and includes studies in combat arnis,

judo, karate, and Western wrestling. Tres Personas arnis is a mixture

of the de marina, de cadena, literada, Batangueña serada, florete,

and sumbrada styles.

In the United States in 1977, Dan Inosanto published

The Filipino Martial Arts. Although not the first book on the arts published

in English, it was the most widely distributed and well-rounded. Inosanto's

early pioneering efforts to expose different Filipino masters and systems

is reflected in this work. Then, in 1978, Kyokushin-kai karate instructor

Ben Singleton sponsored the Pro-Am Classic tournament in Vista, California.

This tournament featured the first full contact open weapons sparring

division in the United States. Narrie Babao, a student of Carlito A. Lañada

and Dan Inosanto, took first place. On March 24, 1979, the National Arnis

Association of the Philippines sponsored the First Open Arnis Tournament

in Cebu City, where Tom Bisio reigned as champion. Then, on August 19,

NARAPHIL sponsored the First National Invitational Arnis Tournament in

Manila. Among the masters who par-ticipated in the "masters sparring

division" were Cacoy Cañete from Cebu, Timoteo Maranga and

Alfredo Mangcal from Mindanao, Jose Mena, Benjamin Luna Lema and Florencio

Pecate from Manila, and Hortencio Navales from Negros Occidental. In Both

tournaments Cacoy Cañete reigned as champion. Interestingly, the

most infamous master, Antonio Ilustrisimo, published

The Filipino Martial Arts. Although not the first book on the arts published

in English, it was the most widely distributed and well-rounded. Inosanto's

early pioneering efforts to expose different Filipino masters and systems

is reflected in this work. Then, in 1978, Kyokushin-kai karate instructor

Ben Singleton sponsored the Pro-Am Classic tournament in Vista, California.

This tournament featured the first full contact open weapons sparring

division in the United States. Narrie Babao, a student of Carlito A. Lañada

and Dan Inosanto, took first place. On March 24, 1979, the National Arnis

Association of the Philippines sponsored the First Open Arnis Tournament

in Cebu City, where Tom Bisio reigned as champion. Then, on August 19,

NARAPHIL sponsored the First National Invitational Arnis Tournament in

Manila. Among the masters who par-ticipated in the "masters sparring

division" were Cacoy Cañete from Cebu, Timoteo Maranga and

Alfredo Mangcal from Mindanao, Jose Mena, Benjamin Luna Lema and Florencio

Pecate from Manila, and Hortencio Navales from Negros Occidental. In Both

tournaments Cacoy Cañete reigned as champion. Interestingly, the

most infamous master, Antonio Ilustrisimo,

refused to compete under the tournament's rules. In response, Ilustrisimo

made the statement: "If anyone wants to take my reputation, they

will have to fight me with a sword." There were no challengers.

The 1980s saw a number of tournaments sponsored to further establish

arnis as a sport. On March 16, 1985, the Third National Arnis Tournament

was held in Cebu City, and the Fourth National in Bacolod City on July

26, 1986. Then, on January 2, 1987 Dionisio "Diony" Cañete,

the nephew of Cacoy Cañete, was elected as the new president of

NARAPHIL. From May 26-29, 1989, the Philippine Kali Grand Championship

was held in Manila. Both events were jointly sponsored by the Kali Association

of the Philippines and the Armed Forces of the Philippines. In response

to the world wide spread of Filipino martial arts the World Kali Eskrima

Arnis Federation (WEKAF) was founded in 1987 in Los Angeles, California,

with Dionisio Cañete as its first president. The First United States

National Eskrima Kali Arnis Championships was then held in San Jose, California

in October of 1988. The First Eastern USA Eskrima Kali Arnis Championships

was then held in New Jersey in May of the following year. Then, on August

11-13, 1989, WEKAF sponsored the First World Kali Eskrima Arnis Championships

in Cebu, Philippines.

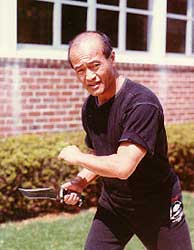

One of the best-known grandmasters of arnis in the Western world is Remy

Presas.

Presas first gained popularity in the United States in 1983, with th

epublishing of his third book, Modern Arnis: Filipino Art of Stick Fighting.

As a result of this book, Presas became known as the "Father of Modern

Arnis," and has since been featured on the cover of numerous martial

arts magazines, produced six instructional video tapes, and has a larger

base of students around the world than any other single Filipino master.

In 1991, Arnis Philippines became the "official" government-sponsored

organization to spread the art of arnis. Arnis Philippines then became

the thirty-third member of the Philippine Olympic Committee. Through this

organization's efforts Arnis was featured as a demonstration sport in

the 1991 Southeast Asian Games (SEA Games). Arnis Philippines then formed

the International Arnis Federation which brought thirty countries together

to work towards the acceptence of asnis as a demonstration sport in the

Olympic games. With arnis now the national sport of the Philippines, the

Senate Committee on Youth and Sports Development, the Philippine Sports

Commission, and the Philippine Olympic Committee jointly sponsored and

endorsed the Grand Exhibition of Martial Arts in Manila. The event, held

on July 31, 1993, featured demonstrations by practitioners of arnis Lanada,

sikaran, kali Ilustrisimo, sagasa, ngo cho kun, pencak silat, hwarangdo,

hsing-i, and kyokushin-kai.

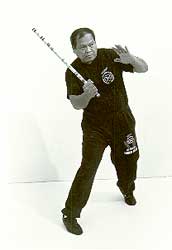

The 1990s also saw many other masters coming out of the woodwork to teach

or further promote their arts.

Included in this group would be the late founder of lameco eskrima, Edgar

Sulite,

Balintawak arnis cuentada master Bobby Taboada,

arnis and hilot master Sam Tendencia, and

Rigonan-Estalilla kabaroan grandmaster Ramiro Estalilla.

The 20th-century has seen a revival of martial arts in the Philippines

paralleled by no other country. In the past sixty years the arts went

from almost complete isolation and obscurity to world wide exposure and

commercialization. With this exposure, and paralleling the ethnic, tribal,

and religious separateness in the Philippines, have sprung a plethora

of new organizations and associations, new schools and styles, new masters

and grandmasters. What the Filipino martial arts needs if they are to

remain through the next century is a stronger sense of cohesion. One organization

must be crafted to accommodate the various martial ideologies. A single

ranking structure must be adopted to assure a high standard for and legitimization

of rank among and between systems and styles. This must happen without

losing sight of the roots of the arts which commercialization tends to

do.

In closing, the words of Leonard B. Meyer are fitting:

"New styles and techniques, schools and movements, programs and

philosophies, have succeeded one another with bewildering rapidity. And

the old has not, as a rule, been displaced by the new. Earlier movements

have persisted side by side with later ones, producing a profusion of

alternative styles and schoolsóeach with its attendant aesthetic

outlook and theory."

About the Author

Mark Wiley is an accomplished martial artist and leading authority

on a variety of Philippine and Chinese martial arts, French savate,

tae kwon do and karate. He is the author of three books on Phillippine

martial arts, including Filipino Martial Culture, from which this article

was in part excerpted. He has served as Martial Arts Editor for Charles

E. Tuttle Publishing Co., Book Publishing Editor for Unique Publications,

Editor of Martial Arts Legends magazine and Associate Editor for the

Journal of Asian Martial Arts. He is author of eight books on martial

arts and qi gong and over 100 articles published in a variety of martial

arts magazines. He also serves as Associate Editor for FightingArts.com.

|