Kagami Biraki: Renewing the Spirit

By Christopher Caile

Kagami Biraki, which literally means “Mirror Opening” (also known as the “Rice Cutting Ceremony”), is a traditional Japanese celebration that is held in many traditional martial arts schools (dojos) usually on the second Saturday or Sunday of January so all students will be able to attend. (1) It was an old samurai tradition dating back to the 15th century that was adopted into modern martial arts starting in 1884 when Jigora Kano (the founder of judo) instituted the custom at the Kodokan, his organization’s headquarters. (2)

Since then other Japanese arts, such as aikido, karate, and jujutsu, have adopted the celebration that officially kicks off the new year — a tradition of renewal, rededication and spirit.

In Japan Kagami Biraki is still practiced by many families. It marks the end of the New Year’s holiday season which is by far the biggest celebration of the year — something which combines the celebration of Christmas, the family orientation of Thanksgiving, mixed with the excitement of vacation and travel.

It is a time when the whole nation (except for the service industries) goes on holiday. It is also a time for family and a return to traditional roots — prayers and offerings at the Shinto shrine and Buddhist Temples, dress in kimonos, traditional food and games. It is also a time when fathers are free to relax and share with the family, to talk, play games, eat and in more modern times, watch TV. It is also a time for courtesy calls to business superiors and associates as well as good customers. Work begins about a week into the month, but parties with friends and co-workers continue. (3)

In most traditional dojos preparation for the new year’s season begins as in most households. Toward the end of the year dojos are cleaned, repairs made, mirrors shined and everything made tidy. In Japan many dojos retain the tradition of a purification ceremony. Salt is thrown throughout the dojo, as salt is a traditional symbol of purity (goodness and virtue), (4) and then brushed away with pine boughs.

Decorations are then frequently placed around the dojo. In old Japan they had great symbolism, but today most people just think of them as traditional holiday decorations.

The dojo’s spiritual center with holiday decorations. At top the miniature shrine is flanked with pine boughs set in vases. Below, on the left, is a display of holiday rice-cakes (Kagami Mochi). At middle is a replica of a samurai armored helmet and at right a ceremonial sake keg, another holiday symbol.

Other decorations are called kadomatsu, which include bamboo (a symbol of uprightness and growth), plum twigs (a symbol of spirit) and pine boughs (from the mountains that are symbols of longevity). Pine boughs are placed around the dojo, principally on doors and in small vases to both sides of the kamidana which is a miniature wooden Shinto shrine (usually set on a shelf high on the ceremonial center). Pine boughs are the only ornamentation not removed after Kagami Biraki.

Another decoration is Shimenawa which is made of twisted strands of rice straw. It is often found on the dojo’s front door or over the entrance to the dojo’s practice floor. This is a symbol of good luck and traditionally it was believed it would help keep evil out.

For martial arts students today, however, the New Year’s celebration of Kigami Biraki has no religious significance. It does, however, continue the old samurai tradition of kicking off the new year. It is also a time when participants engage in a common endeavor and rededicate their spirit, effort and discipline toward goals, such as training.

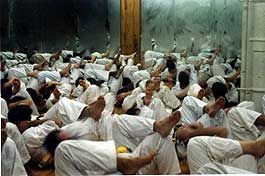

At our World Seido Karate Headquarters hundreds of students congregate early in the morning to train together, although it gets so crowded that real training is difficult. Practice thus become more a sharing of spirit, as New Years is expressed amongst the push-ups, kiais (shouts) and many repetitions of technique. As effort and sweat builds, a steamy mist rises among the participants. There is also a message from our founder, Kaicho Tadashi Nakamura, followed by short speeches by senior dojo members. The celebration ends with refreshments (which can be viewed as a symbolic representation of the traditional rice cake breaking and consumption) and a meeting of all teachers and Branch Chiefs.

At our World Seido Karate Headquarters hundreds of students congregate early in the morning to train together, although it gets so crowded that real training is difficult. Practice thus become more a sharing of spirit, as New Years is expressed amongst the push-ups, kiais (shouts) and many repetitions of technique. As effort and sweat builds, a steamy mist rises among the participants. There is also a message from our founder, Kaicho Tadashi Nakamura, followed by short speeches by senior dojo members. The celebration ends with refreshments (which can be viewed as a symbolic representation of the traditional rice cake breaking and consumption) and a meeting of all teachers and Branch Chiefs.

In other schools the celebration is very different. Ernie Estrada, Chief Instructor of Okinawan Shorin-ryu Karate-do, reports that their Kagami Biraki is highlighted by a special “Two Year Training.” This includes ten to twelve hours of intense training, the length and severity symbolically representing the two year time span.

George Donahue, a student of the late Kishaba Chokei and Shinzato Katsuhiko, and former director of Matsubayashi Ryu’s Kishaba Juku of New York City, notes that in Japan Kagami Baraki started with a long morning session of zazen (kneeling meditation), and includes visits to the dojo throughout the day by well-wishers, ex-students, and local politicians. The day is ended with an especially intense workout followed by a long party attended by dojo members and honored guests from the community. After three or four hours of speeches, toasts, eating, and drinking, people demonstrate their kata. For non-local students this is usually the only opportunity in the year to receive a promotion.

For old style teachers who don’t officially charge for instruction, Kagami Biraki has special significance. It is a day for students to anonymously honor their teachers with cash gifts. Contributions are placed within identical envelopes with no contributor identification, and discreetly left in a pile for the teacher. (6)

The Ancient New Year’s Observance

The Japanese New Year’s tradition has its roots in the ancient folk beliefs of agrarian China. If a bountiful harvest was desired, it was thought necessary to first create a warm, human atmosphere into which the harvest would grow. Critical to this process were the bonds of family and community based on blood, obligation and work that were further strengthened during this holiday from common celebration and sharing.

In Japan this tradition further evolved into a Shinto celebration based primarily around the worship of a deity Toshigama, (7) (thought to visit every household in the new year) in order to insure the production of the five gra`ins: rice, wheat barley, bean and mullet.

In preparation for the deity’s visit, people cleaned and then decorated their homes to beautify them for the diety. There were also prayers and ringing of temple bells to ward off evil spirits. New Years was initiated with visits to Shrines and family and ritual ceremonies — all revolving around Toshigama. While today the meaning of most of these Shinto observances has been forgotten, many of rituals remain in the form of holiday traditions.

The symbolism of the mirror, which is central to Kagami Biraki, dates back to the original trilogy myth (along with the sword and the jewel) of the creation of Japan. By the 15th century Shinto had interpreted the mirror and sword to be important symbols of the virtues that the nation should venerate. (8) They also symbolized creation, legitimacy and authority of the Emperor and by extension the samurai class itself as part of the feudal system.

The mirror enabled people to see things as they are (good or bad) and thus represented fairness or justice. The mirror was also a symbol of the Sun Goddess — a fierce spirit (the light face of god).

Swords had long been given spiritual qualities among the samurai. And their possession contributed to a sense of purpose and destiny inherent within the samurai culture. So legendary were some swords that they were thought to posses their own spirit (kami). (9)

Considered as one of the samurai’s most important possessions, the sword (and other weapons) symbolized their status and position. Firm, sharp and decisive, the sword was seen as a source of wisdom and venerated for its power and lightning-like swiftness, but it was also seen as a mild spirit (the dark face of god).

Taken together, the mirror and sword represent the Chinese yin and yang, or two forms of energy permeating everything — the primeval forces of the universe from which everything springs — the source of spirit empowering the Emperor by extension samurai class who was in his service.

The Beginning of Kagami Biraki

It was from this time (15th century), it is said, that the tradition of Kagami Biraki began. It developed as a folk Shinto observation with a particular class (samurai) bent. (10)

Before the New Year Kagami Mochi, or rice cakes, were placed in front of the armory (11) to honor and purify their weapons and armor. On the day of Kagami Biraki the men of Samurai households would gather to clean, shine and polish their weapons and armor (12).

So powerful was the symbol of armor and weapons that even today links to these feudal images remain. Japanese households and martial arts dojos often display family amor (family kami), helmets or swords, or modern replica, displayed in places of honor. In front of these relics, sticks of incense are burned to show honor and acknowledge their heritage.

Women in samurai households also placed Kagami Mochi, or rice cakes, in front of the family Shinto shrine. A central element (set in front of the Shrine) was a small round mirror made of polished silver, iron, bronze or nickel. It was a symbol of the Sun Goddess, but was also thought to embody the spirits of departed ancestors. So strong was this belief that when a beloved family member was near death, a small metal mirror was often pressed close to the person’s nostrils to capture their spirit. (13)

The round rice cakes were thus used as an offering — in gratitude to the deities in the hope of receiving divine blessing and also as an offering to family spirits (and deceased family heroes). It was thought that this offering would renew the souls of the departed to which the family shrine was dedicated. (14)

To members of Japanese feudal society mirrors thus represented the soul or conscience. Therefore it was considered important to keep mirrors clean since it was thought that mirrors reflected back on the viewer his own thoughts. Thus the polishing of weapons and amor on Kagami Biraki was symbolically (from mirror polishing) seen as a method to clarify thought and strengthen dedication to samurai’s obligations and duty in the coming year. Thus Kagami Biraki is also known to some as “Armor Day.”

This concept continues even today. When your karate, judo or aikido teacher talks of self-polishing, of working on and perfecting the self and to reduce ego, the concept harkens back to the ancient concept of mirror polishing to keep the mind and resolve clear.

On Kagami Baraki, the round rice cakes (often specially colored to represent regions or clans) would be broken, their round shape symbolizing a mirror and their breaking apart symbolizing the mirror’s opening. The cakes were then consumed in a variety of ways.

The breaking of rice-cakes (Kagami Mochi) on Kagami Biraki symbolizes the coming out (of a cave) of the Sun Goddess in Japanese mythology, an act that renewed light and spirit to the ancient world. (15). Thus breaking apart the rice cakes each year on this date represents a symbolic calling out again of this life force and reenactment of the beginning (mythological) of the world. (16)

The Kagami Mochi are consumed. This is seen as an act of spiritual communion. It was believed that partaking of these cakes not only symbolized the renewal of the souls of their ancestors, but also the absorption of the spirit (or aura) Toshigama (also probably the Sun Goddess) to which the New Years season was dedicated. For this reason eating Kagami Mochi has always represented renewal, the start of the new year and the first breaking of the earth or the preparation for coming agriculture. Thus consumption was a physical act of prayer, happiness and peace in the new year in the spirit of optimism, renewal and good luck. The new year was thus seen with hope, and full of fresh possibility, a clean beginning and opportunity for dedication.

There were also very human benefits. The sharing of rice cakes with family and clan members helped strengthen common ties and bonds of allegiance and friendship among warriors. Rice cakes also prepared the body for the new year.

The new year holiday was most often filled with drinking, celebration and eating ceremonial foods. On January 7, the body was first fortified with a special rice herbal concoction that was thought to cure the body of many diseases. Thus, by Kagami Biraki people’s bodies were ready for regulation and cleansing. Mocha was often eaten with different edible grasses for this purpose. It prepared people to resume a regular schedule.

The very rice consumed itself had symbolic meaning for the Samurai. Farmers once thought that rice having breath (actually breathing in the ground), thus giving rise to the concept of rice being “alive,” (breathing in the field), and thus divine imbued with a living deity (kami). On another level rice represented the very economic backbone of the samurai society. It was given to the samurai as a stipend in return for service and allegiance to his lord (or alternatively given control over land and peasants who produced rice) — in a society where wealth and power were not based on currency, but on control of land which produced agriculture.

In recent years some people have reinterpreted the “Mirror Opening Ceremony” from a different viewpoint, Zen. In the book, Angry White Pajamas – An Oxford Poet Trains with the Tokyo Police, the author Robert Twigger recounts as an interpretation of Kagami Biraki an esoteric explanation given to him by someone who had lived in a Zen monastery. The mirror, it was explained, contains an old image, for what one sees in the mirror is seen with old eyes. You see what you expect to see, something that conforms with your own self-image based on what you remember of yourself. In this way the eyes connect people with their past through the way they see their own image. This creates a false continual. Instead every moment holds potential for newness, another possibility for breaking with the old pattern, the pattern being just a mental restraint, something that binds us to the false self people call “me.” By breaking the mirror one breaks the self-image that binds people to the past, so as to experience the now, the present. “This is Kagami Biraki,” recounts Twigger, “a chance to glimpse the reality we veil with mundaneness of day-to-day living.”

Also See:

Kagami Biraki 2001

Photo Portrait

About the Author Christopher Caile

Screenshot

Christopher Caile is the Founder and Editor-In-Chief of FightingArts.com. He has been a student of the martial arts for over 65 years.

He first started in judo while in college. Then he added karate as a student of Phil Koeppel in 1959 studying Kempo and Wado-Ryu karate. He later added Shotokan Karate where he was promoted to brown belt and taught beginner classes. In 1960 while living in Finland, Caile introduced karate to that country and placed fourth in that nation’s first national judo tournament.

Wanting to further his karate studies, Caile then hitch hiked from Finland to Japan traveling through Scandinavia, Europe, North Africa, the Middle East and South and Southeast Asia — living on 25 cents a day and often sleeping outside.

Arriving in Japan (1962), Caile was introduced to Mas Oyama and his fledgling full contact Kyokushinkai Karate by Donn Draeger, the famous martial artist and historian. Donn also housed him with several other senior international judo practitioners. Donn became Caile’s martial arts mentor, coaching him in judo and introducing him to Shinto Muso-ryu under Takaji Shimizu.

Caile studied at Oyama’s honbu dojo and also at Kenji Kurosaki’s second Tokyo Kyokushinkai dojo. In his first day in class Oyama asked Caile to teach English to his chief instructor, Tadashi Nakamura. They have been friends ever since. Caile also participated in Oyama’s masterwork book, “This Is Karate.”

Caile left Japan with his black belt and designation as Branch Chief, the first in the US to have had extensive training in Japan directly under Oyama Sensei. As such, Oyama Sensei asked him to be his representative on visits to his US dojos to report on their status.

A little over a year later, Nakamura, Kusosaki and Akio Fujihira won an epic David vs. Goliath challenge match against Thailand’s professional Muay Thai Boxers in Bangkok, Thailand, thrusting Kyolushinkai and Nakamura into national prominence.

Back in the US Caile taught Kyokushinkai karate in Peoria, Il while in college and later in Washington, DC. while in graduate school. Durimg this time Shihan Nakamura had moved to New York City to head Kyokushinkai’s North American Operation.

In 1976 when Kaicho Tadashi Nakamura formed the World Seido Karate organization, Caile followed. Living then in Buffalo, NY, Caile taught Seido karate and self-defense at the State University of New York at Buffalo (SUNY Buffalo) for over 15 years where he also frequently lectured on martial arts and Zen in courses on Japanese culture.

Caile moved to New York City in 1999 to marry Jackie Veit. He is now an 8th degree black belt, Hanshi, training in Seido Karate’s Westchester, NY Johshin Honzan (Spiritual Center) dojo. In Seido Caile is known for his teaching of and seminars on kata applications. He also produced a 14 segment video series on Pinan kata Bunkai currently available to Seido members.

Caile is also a long-time student and Shihan in Aikido. He studied in Buffalo, under Mike Hawley Shihan, and then under Wadokai Aikido’s founder, the late Roy Suenaka (uchi deshi under Morihei Ueshiba, founder of Aikido and was Shihan under Tohei Sensei). In karate, Suenaka (8thdan) was also an in-house student of the Okinawan karate master Hohan Soken.

Having moved to New York City, Caile in 2000 founded this martial arts educational website, FightingArts.com. Twenty-five years later, in 2025, it underwent a major update and revision.

For FightingArts.com and other publications Caile wrote hundreds of articles on karate, martial arts, Japanese art, Chinese Medicine and edited a book on Zen. He also developed relationships with a cross section of leading martial arts teachers. Over the last four decades he has conducted extensive private research into karate and martial arts including private translations of the once secret Okinawan hand copied and passed on Kung Fu book, the Bubishi, as well as an early karate book by the karate master Kenwa Mabuni. He periodically returns to Japan and Okinawa to continue his studies and participate Seido karate events. In Tokyo he practiced (with Roy Suenaka Sensei) in a variety of aikido organizations with their founders – including private interviews and practices at the Aiki-kai Aikido Honbu dojo with the son and grandson of aikido’s founder, Doshu (headmaster) Kisshomaru (an old uchi-deshi friend) and his son, Moriteru Ueshiba and in Iwama with Morihiro Saito. On Okinawa he studied Goju Ryu karate under Eiichi Miyazato, 10th dan founder of Naha’s Jundokan, and also with Yoshitaka Taira (who later formed his own organization, who specialized in kata Bunkai. While there Caile also trained with Hohan Soken’s senior student, Master Fusei Kise, 10 dan as well as with the grandson of the legendary karate master Anko Itosu.

Caile’s other martial arts experience includes: Diato-ryu Aikijujitsu and Kenjitsu, kobudo, boxing, Muay Thai, MMA, Kali (empty hand, knife and bolo), study of old Okinawan Shoran-ryu & Tomari body mechanics, study of old Okinawan kata under Richard Kim, study of close quarter defense and combat, including knife and gun defenses, Kyusho Jitsu and several Chinese fighting arts including 8 Star Praying Mantis, Pak Mei (White Eyebrow), and a private family system of Kung Fu.

Caile is also a student of Zen as well as a long-term student of one branch of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chi Kung (Qigong). As one of two senior disciples of Chi Kung master Dr. Shen (M.D., Ph.D.) Caile was certified to teach and practice. This led to Caile’s founding of the The Chi Kung Healing Institute on Grand Island, NY. In Western NY, he also frequently held Chi Kung seminars, including at SUNY Buffalo and at the famous Chautauqua Institution in Chautauqua, NY. His articles on Chi Kung also appeared in the Holistic Health Journal and in several books on alternative medicine.

Caile holds a BA in International Studies from Bradley University and MA in International Relations with a specialty in South and Southeast Asia from American University in Washington, D.C. While in Buffalo, NY he also studied digital and analog electronics.

In his professional life Caile also worked in public relations and as a newspaper reporter and photographer. Earlier he worked in the field of telecommunications including Managing a Buffalo, NY sales and service branch for ITT. He then founded his own private telephone company. This was followed by creation of an electrical engineering company that designed and patented his concept for a new type of low-cost small business telephone system (which was eventually sold to Bell South). The company also did contract work for Kodak and the US space program. Simultaneously Caile designed and manufactured a unique break-apart portable pontoon boat.

Most recently Caile co-founded an internet software company. Its products include software suites with AI capability for control and management of streaming media, such as video and music, an all-in-one book publishing software product for hardcover, eBook and audio book creation and security software for buildings and government use.

For more details about Christopher Caile’s martial arts, work experience and life profile, see the About section in the footer of this site.

Search for more articles by this author: