Keppan – The Blood Oath: Part 1

By Dave Lowry

Editor’s Note: This is first of a two part article. Part 1 discusses the distinctive nature and exclusivity of Samurai fighting arts during Japan’s feudal period, and how samurai’s admittance to a school (ryu) of training often required him to sign an oath of allegiance to the martial arts organization. Part 2 delves deeper into the nature of this commitment while also comparing the nature of warrior training in feudal Japan to that of today’s new martial arts such as judo, aikido, karate, and kendo within which such allegiances are no longer practical.

“Now, we’ll start with this band of robbers and call it Tom Sawyer’s gang. Everybody that wants to join has to take an Oath, and write his name in blood.”

–Mark Twain, The Adventures Of Huckleberry Finn

Every since Hollywood discovered the martial arts as a medium for attracting viewers, audiences for TV programs and movies have been entertained with all sorts of fanciful plots which involve the hero gaining admittance into a secret school of fighting arts, a task at which he succeeds only after enduring some sort of tests of his commitment and resolve.

It is always a period of initiation and he must prove himself worthy of the tradition he is about to enter. The master is always reluctant to teach him, the art is ever so secret and rare, and so this process tends to be mysterious and arduous, dramatic and frequently painful.

The truth is, in the case of most classical martial koryu (classical martial arts, systems begun before the beginning of the “modern” Meiji era (1868), invariably a bit less theatrical. In the first place, the typical aspirant to a school of martial art in the feudal age was, almost without exception, a member of the samurai or warrior class.

Non-warriors, farmers, merchants, artisans; these people had little time to pursue the exacting and exhaustive study of fighting on a battlefield and of course, they would have had little reason to want to. Non-martial fighting arts, e.g, karate, kung-fu, etc., have virtually no place in the scheme of combative skills in Japan. Fighting in that country during the feudal period was considered to be the work of professional men-at-arms. These were men employed by feudal lords as a kind of standing army. Therefore, it was to the advantage of those lords, or daimyo, to retain martial arts teachers among their vassals. The preponderance of martial koryu were attached in one way or another, to specific daimyo or powerful military families. So, if you were a young man of the samurai rank retained by say, the house of Suzuki, then you would automatically go for martial training to the ryu (a martial arts tradition) that was under the auspices of the Suzuki clan. You didn’t have to sit out in the rain for days waiting to get his attention. Or mutilate yourself as a sign you had been accepted.

In some cases, however, a martial ryu may have been more or less independent of its headmaster, even if he was a retainer of a particular daimyo, may have had his lord’s permission to accept whatever students he liked. When an aspirant martial artist approached a master with whom he had no formal connection requesting admission into the master’s system, he would, if at all possible, bring a letter of introduction, or shokai. The shokai would have been written by someone known to and trusted by the master, attesting to the character and aptitude of the would-be student. Even if this letter was presented and accepted, it was not uncommon for the student to be put off in one way or another.

Masters in the classical martial ryu had their own personalities, of course, just like the rest of us. And when you stop to think about it, someone who devoted the majority of his waking hours in training in ways to shorten the lives of others by violent means could be expected to have his share of behavioral quirks. These men could be obtuse in accepting a new pupil. Everyone is surely aware, in one form or another, of the story of the master who accepted a student only to have the student perform cooking and cleaning tasks. When the student was thus engaged, the master would sneak up and fetch him a whack with a stick, appearing at odd times and always trying to catch the student off his guard.

|

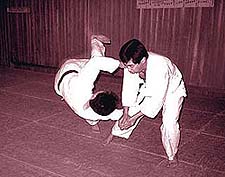

Takeuchi-ryu students practice a throwing technique. Students in this ryu continue to sign keppan to seal an oath to the ryu. Photo by Wayne Muromoto |

Eventually, so the story goes, the student learns that the increased awareness he learns through this training is a kind of mastery itself. It’s a nice story and perhaps may have some basis in historical fact. But the truth is, the warrior in the era of Sengoku (“Warring States” period) needed to acquire skills that would keep him alive on the battlefield, in fights that could come at any time. Unlike the practitioner of Zen Buddhism, who could kill a decade or two in seeking enlightenment, the warrior needed at least an introduction to the practicalities of a combative art rather quickly. And so instruction in a martial art was at least begun with the students’ being accepted into the ryu, in most cases.

Before beginning his training, however, it was common for this student to be required to sign an oath of allegiance to the ryu. It is very difficult to convey the seriousness with which these oaths were undertaken. We live in a world in which individuals routinely swear to tell the truth in courts of law and go right on to tell the most outrageous of falsehoods. We live In an increasingly non-secular world in which the idea of pledging fealty to some higher being (or even, in the case of marriage vows and such, to one another) is quaint at best. In order to understand just how serious these oaths were, one must understand first that nearly all martial ryu had deep and strong connections with their own, particular deities, mostly Buddhist, some of Shinto origin. These were supernatural patrons of the ryu and it was to them that one made his oath.

Reproduced with permission of Dave Lowry. Copyright © Dave Lowry & FightingArts.com. All Rights Reserved.

This article first appeared in Furyu the Budo Journal #8.

Dave Lowry

Dave is an American writer best known for his articles, manuals and novels based on Japanese martial arts.

Mr. Dave Lowry literally grew up in the Japanese cultural arts. As a boy, he commenced a lifelong study of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu swordsmanship under a Japanese teacher who was living in Missouri. In 1985, Mr. Lowry’s experiences growing up as a Westerner, who was deeply immersed in Japanese cultural and martial arts, formed the basis for his publications.

In addition to Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, Mr. Lowry has trained in karate-do and a variety of modern martial ways. His current and primary martial arts activities are focused on Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, Shindo Muso Ryu (an old combative art utilizing a four-foot staff), and aikido. He has also practiced a wide variety of Japanese arts including go (an ancient Japanese game), shodo (calligraphy), kado (flower arrangement), and chado (tea ceremony).

Mr. Dave Lowry has a degree in English, and works as a professional writer. He has authored numerous books related to budo the Japanese concept of the “martial way.” He has written training manuals on use of weapons such as the bokken and jo, novels centered on the lifestyle of the budōka (one who follows the martial way), and many articles on martial practices and traditional Japanese philosophy. He has been a regular columnist for Black Belt magazine since 1986, where he writes on the traditional arts and has contributed to FightingArts.com. He has also served as Senior Advisor to the SMAA (and contributor to its Journal), an organization dedicated to providing realistic survival orientated defense training and education.

Search for more articles by this author: